Seed-planting and Fruit Bearing

/Adoration of the Shepherds by Dutch painter Matthias Stomer, 1632

A Twilight Musing

During the Christmas Season we concentrate on the beginning of God’s greatest act of seed-planting, the impregnation of Mary by the Holy Spirit. We do well, however, to remember that the immediate fruit of her womb, the birth of the Incarnate Son of God was not the end of the matter, but the beginning of the ever-expanding purposes of God through His Son. The poem below depicts Mary’s awareness that her understanding of what has happened to her will be an unpredictable unfolding.

The Husbandry of God

(Luke 1:26-35)

How can I contain this word from the Lord?

His light has pierced my being

And sown in single seed

Both glory and shame.

Content was I

To wed in lowliness

And live in obscurity,

With purity my only dower.

Now, ravished with power,

I flout the conventions of man

To incubate God.

In lowliness how shall I bear it?

In modesty how shall I tell it?

What now shall I become?

But the fruit of God's planting

Is His to harvest.

No gleaner I, like Ruth,

But the field itself,

In whom my Lord lies hid.

“What now shall I become?” she asks, and realizes that, like the embryo in her womb, the purposes of God are developing. When the baby is born and the shepherds make their surprise visit, Mary “pondered” the meaning of the message they brought (Luke 2:19). She must also have pondered the cryptic words of Simeon in the Temple when Mary and Joseph brought the baby to be dedicated to the Lord: that in addition to being “appointed for the fall and rising of many in Israel,” that also “a sword will pierce through your [Mary’s] own soul” (Luke 2:33-35). When Mary said, “Let it be done to me according to your word” (Luke 1:38), she was letting herself in for more than she realized. Those of us who have walked with the Lord for a while recognize that He often takes what seems submission to his will for a specific time and expands it into a much longer period of the development of His purposes.

This sense of God’s ends being incipient in His beginnings is brought out beautifully and profoundly in the first 18 verses of John 1. I have endeavored to create below a poetic digest of these verses.

“The Alpha/Omega Word”

(John 1:1-18)

Beginning Word

Spoke Light to Chaos;

Light pushed Life from sod,

And God through Word

Made forms to walk on sod,

And finally man to trod

On finished earth.

But darkness pierced

The perfect pearl of Paradise:

The Word no longer heard,

Nor known the fellowship with Light.

In darkness, tyrannous Time was lord,

But Time was also womb of Light renewed.

Word of Light

Re-entered world He made,

Took on a mortal mould1

That showed the face of God,

Undimmed by shade.

Heralded by John He came,

Following in flesh

But eternally before;

Jordan-witnessed Lamb of God,

Light to be extinguished

So that Light could shine once more.

Time redeemed

Became a womb again:

Spirit spawned

Brothers of the Son,

Children owing naught to fallen flesh,

But reborn through God-in-Flesh,

The Light of Life.

New Covenant of Life,

Bought with blood,

Became God’s family,

Receiving grace and truth

Transcending Law of Death.

New breath breathed in

Through timeless Word,

Beginning and also end.

1 “Mould” is the British spelling of “mold,” with

the old meaning of “earth” (decaying material).

In this poem, we see encapsulated the maturing of God’s eternal purpose in cycles of renewal: Word creating flesh finally becoming flesh to redeem fallen flesh; Light dimmed by darkness, but Light piercing darkness; the tyranny of time and death reversed by Incarnate eternality; fallen flesh becoming like the Son of God, recreated in the image of the Word Himself.

Praise in this season for our wondrous God, not only as the Alpha born of Mary, but as the Omega still working out His purposes in us and in the world.

Dr. Elton Higgs was a faculty member in the English department of the University of Michigan-Dearborn from 1965-2001. Having retired from UM-D as Prof. of English in 2001, he now lives with his wife and adult daughter in Jackson, MI.. He has published scholarly articles on Chaucer, Langland, the Pearl Poet, Shakespeare, and Milton. His self-published Collected Poems is online at Lulu.com. He also published a couple dozen short articles in religious journals. (Ed.: Dr. Higgs was the most important mentor during undergrad for the creator of this website, and his influence was inestimable; it's thrilling to welcome this dear friend onboard.)

Good King Wenceslas: An Allegory of Advent

/Good King Wenceslas, illustrated in Christmas Carols, New and Old

One Advent night in 1982 we attended a Christmas choral concert in the Bristol Cathedral in England. Though I knew the “Good King Wenceslas” carol, I had never paid attention to the lyrics. That night the majestic orchestra, joined with the cathedral choristers and choir, dramatized the Wenceslas lyrics in such a way the joy and awe of the Gospel message transfixed me. As we share verse by verse this carol’s allegory, rejoice this Christmas season. God entered His world to rescue helpless souls like you and me!

Stanza One

Good King Wenceslas look’d out, On the feast of Stephen,

When the snow lay round-a-bout, Deep and crisp and even.

Brightly shone the moon that night, Though the frost was cruel,

When a poor man came in sight, Gath’ring winter fuel.

On the Feast of St. Stephen’s, the day after Christmas or “Boxing Day,” the celebrations of giving and receiving continue. King Wenceslas is comfortably settled in his great castle. Fifteen-foot Christmas fir trees grace the palace drawing rooms with their candlelight and royal baubles. Holly and berry swags adorn huge fireplace mantels. Golden candelabras throw flickering warmth across the hall. The king’s fireplaces blaze with forest logs. His vast tracts of woodlands and forest supply against the coldest winter nights. The king’s massive palace radiates with family cheer and contentment. He lacks for nothing.

Good King Wenceslas embodies God. Sovereign of worlds seen and unseen, He commands seventy sextillion known stars. He is Monarch of more shining, heavenly spheres than ten times the grains of sand on earth’s deserts and beaches. The earth is His and “everything in it, the world, and all who live in it.” “For every beast of the forest is mine,” says the Lord. Wenceslas’ kingdom is the cosmos resplendent with light, order, and plenty.

The St. Stephen’s winterscape captivates the eye – at least from the sovereign’s side of the window pane. Contented after a day of festivities, King Wenceslas looks out. The snow is “deep and crisp and even,” glistening in the moonlight. The idyllic picture is betrayed by the fierce cold. No one dare venture out on a night like this; yet, against the snow a dark figure intrudes into the king’s gaze. What’s that man doing out there on a night like this? Rummaging for wood on the holiday? Why does he not have wood? Was he slack in stocking up in the summer? Now he is come to trespass on the king’s property?

This poor man rummaging for wood on a frigid night is every person’s ill state. Prophets painted our picture gloomy: “Cursed is the ground…. Through painful toil you will eat … and the pride of men humbled…. There is an outcry in the streets for lack of wine … all the merry-hearted sigh … people loved darkness … because their deeds were evil.” Ignorance of our blindness and rebellion against God cover like darkness. Human life is lived under sin as “far as the curse is found.” Pitiable and bound to self and fleshly passions the “flood of mortal ills” and evils overtake us. Under the power of sin, ruin and misery overtake our paths. We are the desperate man come into sight scrounging every which way to survive against the cruel winter’s wrath.

Stanza Two

‘Hither, page, and stand by me, If thou know’st it telling,

Yonder peasant, who is he? Where and what his dwelling?’

‘Sire, he lives a good league hence, Underneath the mountain,

Right against the forest fence, By Saint Agnes’ fountain.’

“Come, here, page,” says King Wenceslas to his attendant. “Yonder peasant, who is he, where and what is his home?” Little does the poor peasant know he is being watched, even by the king himself. “The mass of men lead lives of quiet desperation,” said Henry David Thoreau. “God will never see,” they say. “The universe is dumb, stone deaf, and blank and wholly blind.” Oh? Are not “the eyes of the Lord … in every place”? Is not “his eye … on the sparrow?” “Where can I flee from your presence?” asks the Psalmist. Under Pharaoh’s whip, Israel was unaware God was witnessing their misery. “I have observed the misery of my people … I have heard their cry … I know their sufferings,” said the Lord.

King Wenceslas is not gawking. The monarch is moved by the poor man’s need. “I have surely seen the mistreatment of my people … I have heard their groaning,” the Lord God said.

Stanza Three

“Bring me flesh, and bring me wine, Bring me pinelogs hither:

Thou and I shall see him dine, When we bear them Thither.”

Page and monarch, forth they went, Forth they went together;

Through the rude wind’s wild lament And the bitter weather.

One would think the king would snap his fingers, issue a command, and servants would rush to the poor man’s aid. What? The monarch himself is going? “You and I will see him dine, when we bear them thither.” “No sire, this is contrary to protocol. The Royal Court does not enter the peasant’s world.” “My subject’s welfare is my own. Forgo the Court’s couch ... leave the velvet slippers and bring me snow boots.”

Incognito the king goes into the furious night. He takes no retinue of riders, carriages, and security guards. This is no “photo op” for the 6 o’clock news. This is not to win the peasant’s vote.

The poor man’s predicament reveals the God who pities our human condition. “He doesn’t forget the cry of the afflicted…. As a Father pities his children, so the Lord has compassion for those who fear him…. But you, O Lord, are a God merciful and gracious.” Rich King Wenceslas becomes the poor peasant. The punishing night is now his. “Though He was rich, yet for your sakes He became poor, so that by His poverty you might become rich.” Christ who was God gave up everything to enter our world. “The Word was God…. And the Word became flesh and lived among us….”

See the Lord of earth and skies

Humbled to the Dust He is.

And in a Manger lies.

The Creator comes into his own universe. The King enters His own woods. Unheralded and unknown He came to his own home, yet the world did not know Him. He leaves heaven and submits Himself to our sinful existence. He even dies unjustly on a cursed cross to save trespassing sinners. He did it incognito … disguised … rejected … as just another commoner abroad on a foul night.

Stanza Four

“Sire, the night is darker now, And the wind grows stronger;

Fails my heart I know not how; I can go no longer.”

“Mark my footsteps, my good page, Tread thou in them boldly;

Thou shalt find the winter’s rage Freeze thy blood less coldly.”

In stanza four, the king’s page comes to the fore in the story. He is accompanying the king on the mission. Jesus called disciples to accompany Him. They go with Him to join in His mission of salvation. As they go, they encounter opposition. The night grows darker. The winds blow stronger. Opposition intensifies. Inspiration grows weak. The servant can go no farther. “Sire, the night is darker now, And the wind blows stronger, Fails my heart I know not how, I can go no longer.” Ever felt you can go no longer? Sighing you say, “Lord, I have had enough.”

Sheet music of "Good King Wenceslas" in a biscuit container from 1913, preserved at the Victoria and Albert Museum.

The fleshly servant is not up to his Master’s task. Nonetheless, in his/her weakness, the disciple discovers God’s strength. The Master’s greatness is manifest. The King will save the poor soul … and bring His weak disciple along with Him. The Sovereign’s grace, solace, help, encouragement, and strength reveal themselves under affliction. “Mark my footsteps, my good page, Tread thou in them boldly, You shall find the winter’s rage, Freeze thy blood less coldly.” Our Master is ahead of us trodding down the snow, cutting a path, and forming our steps for us. The Master’s very footsteps heat up us servants’ cold.

Stanza Five

In his master’s steps he trod, Where the snow lay dinted;

Heat was in the very sod, Which the saint had printed.

Therefore, Christian men, be sure, Wealth or rank possessing,

Ye who now will bless the poor, Shall yourselves find blessing.

Indeed, the “Good King Wenceslas” carol dramatizes poignantly our Christian responsibility to the poor and disenfranchised. Nevertheless, I see a deeper allegory. The King forgoes his palace to enter a fierce world in order to rescue a helpless man. Christ Jesus leaves heaven, empties Himself, becomes flesh, and suffers death on a cross to save helpless humankind. The Master calls His servants to go with him in His mission of bringing abundant life to endangered sinners in this dark, rude world. We offer Jesus Christ and ourselves to helpless sinners in a frightful world. As we go, He goes with and before us treading out our path.

Tom was most recently pastor of the Bellevue Charge in Forest, Virginia until retiring in July. Studying John Wesley’s theology, he received his M.A. and Ph.D. degrees from the University of Bristol, Bristol, England. While a student, he and his wife Pam lived in John Wesley’s Chapel “The New Room”, Bristol, England, the first established Methodist preaching house. Tom was a faculty member of Asbury Theological Seminary from 1998-2003. He has contributed articles to Methodist History and the Wesleyan Theological Journal. He and his wife Pam have two children, Karissa, who is an Associate Attorney at McCandlish Holton Morris in Richmond, and, John, who is a junior communications major/business minor at Regent University. Tom enjoys being outdoors in his parkland woods and sitting by a cheery fire with a good book on a cool evening.

Editor's Recommendation: The Layman’s Manual on Christian Apologetics by Brian Chilton

/Editor's Recommendation: The Layman’s Manual on Christian Apologetics by Brian Chilton

Recommended by David Baggett

“Chilton’s Manual delivers on its promise to make accessible to the local church the powerful resources of apologetics. Providing an aerial view of the apologetic landscape at once refreshing and required, written with winsomeness and good humor, it shows the author’s pastoral heart, practitioner’s spirit, and rigorous mind. This book can and will equip readers to answer honest questions and gain confidence and boldness in sharing, explaining, and defending the good news of the gospel.”

More Recommendations

Gratitude, Thankfulness, and the Existence of God

/Gratitude, Thankfulness, and the Existence of God

Stephen S. Jordan

Every year around Thanksgiving Day, and also throughout the Christmas season, we pause to reflect on all that we have for which to be grateful. There are other times throughout the year when we sense the need to say thanks, and we realize we ought to be more grateful than we presently are—but do we ever stop and think about how the very nature of gratitude and thankfulness actually point to the existence of God?

Gratitude is the awareness of goodness in one’s life and the understanding that the sources of this goodness lie, at least partly, outside oneself. It is not a self-contained or self-sufficient emotion but rather a human person’s inner response to another person or group of persons for benefits, gifts, or favors obtained from them. For example, consider the gratitude one experiences as a result of loving family members, thoughtful friends, and devoted teachers or mentors. The duty of gratitude is to honor these persons by thanking them for the benefits they have provided. Similarly, when gratitude is felt due to a country, school, or some other collective body, it is owed to them not as impersonal establishments, but as communities of human persons. Therefore, gratitude is a deeply personal emotion directed toward persons or groups of persons.[1]

Thankfulness occurs when one outwardly expresses the inner gratitude that is felt. Like gratitude, thankfulness is personal in nature. The difference between the two lies in that being grateful is a state, whereas thanking is an action.[2] With thankfulness, a personal object is in view when someone receives a special gift from a friend or family member and responds by saying “thank you” or writing a “thank you” card or note. In every expression of thanks, the verb “thank” is used in conjunction with an object—typically with the word “you.” Without an object of thanks, there can be no thankfulness. This means that every time one utters the words “thank you,” it is directed toward someone. Thus, thankfulness is an outward personal response directed toward individual persons or communities of persons.[3]

On a deeper level, when one experiences the richness of life which culminates in a deep sense of gratitude and a profound desire to express thankfulness, to whom is this gratitude, this desire to offer thanks, to be directed? G. K. Chesterton once stated, “The worst moment for an atheist is when he feels thankful and has no one to thank.”[4] Of course, it is easy to understand how an atheist or agnostic feels gratitude toward human persons who have made positive differences in their lives, but what about the blessings that cannot be ascribed to human agency? For example, when one considers the overwhelming immensity of a galaxy or the dynamic intricacy of a single living cell and feels as if they are a part of something special, of something bigger than themselves—to what or whom is this sense of gratitude due? While looking at things like a galaxy or cell, the well-known atheist, Richard Dawkins, admits that he is overcome with an immense feeling of gratitude: “It’s a feeling of sort of an abstract gratitude that I am alive to appreciate these wonders. When I look down a microscope it’s the same feeling. I am grateful to be alive to appreciate these wonders.”[5] An atheist or agnostic finding himself or herself in a situation like that of Dawkins, where gratitude arises and there is no personal being to thank, is presented with a difficult conundrum that is difficult to overcome.

There are a number of other examples that illustrate this same point. For instance, when one drinks a cool glass of mountain spring water after a long hike and experiences refreshment not only of the body but seemingly of the soul, or when one is lying on the beach and enjoys the warmth of the sun beaming down on their skin—to what or whom should this person offer their thanks? In moments like these, is one’s gratitude directed toward impersonal things like galaxies, cells, water or the sun—or is this gratitude more appropriately directed toward a personal God who cares deeply for human persons and makes possible their enjoyment and overall well-being? Does it make sense to offer thanks to a galaxy, a cell, water or the sun for the good gifts of life—or does it make more sense to thank God as the personal Creator and transcendent Giver of all good gifts that we enjoy in life?[6]

In his book Thanks!, Robert Emmons shares a story involving Stephen King, the most successful horror novelist of all-time, where King’s survival of a serious automobile accident causes his heart to become flooded with a deep-seated gratitude that King directs toward God. As Emmons explains,

“In 1999, the renowned writer Stephen King was the victim of a serious automobile accident. While King was walking on a country road not far from his summer home in rural Maine, the driver of a van, distracted by his rottweiler, veered off the road and struck King, throwing him over the van’s windshield and into a ditch. He just missed falling against a rocky ledge. King was hospitalized with multiple fractures to his right leg and hip, a collapsed lung, broken ribs, and a scalp laceration. When later asked what he was thinking when told he could have died, his one-word answer: ‘Gratitude.’ An avowedly nonreligious individual in his personal life, he nonetheless on this occasion perceived the goodness of divine influence in the outcome. In discussing the issue of culpability for the accident, King said, ‘It’s God’s grace that he [the driver of the van] isn’t responsible for my death.’”[7]

Interestingly, as a result of his life being spared, King directs the gratitude that arises in his heart to God. Even though there was another human in view, it would have been odd for King to thank the driver of the van who nearly killed him. If it did not make sense for King to thank the driver of the van, then who else could he thank if not God, who was responsible (in King’s own words) for saving his life on a day when he probably should have died?

The examples above illustrate that there are times when it does not make sense to direct gratitude and offer thanks to human persons. Even those who deny God’s existence and believe that the world is the result of blind, purposeless forces still agree that there are instances of gratitude that reach beyond a human benefactor. One’s sense of gratitude and desire to give thanks does not go away on an atheistic worldview—it is only frustrated.

In these instances (when it doesn’t make sense to thank a human person), we ought to direct our gratitude and thankfulness, even our praise, to God. Indeed, in every moment of every day, in all circumstances (1 Thess. 5:18), our hearts and minds ought to be characterized by gratitude and thankfulness; nothing less is appropriate considering God’s wonderful blessings upon our lives (James 1:17). Our prayer to God ought to be that of the Welsh poet and priest of the Church of England, George Herbert, who wrote,

“Thou that hast given so much to me,

Give one thing more, a grateful heart.”[8]

Stephen S. Jordan currently serves as a high school Bible teacher at Liberty Christian Academy in Lynchburg, Virginia. He is also a Bible teacher, curriculum developer, and curriculum editor at Liberty University Online Academy, as well as a PhD student at Liberty University. Prior to his current positions, Stephen served as youth pastor at Pleasant Ridge Baptist Church in State Road, North Carolina. He and his wife, along with their three children and German shepherd, reside in Goode, Virginia.

Notes:

[1] According to Robert Emmons, a leading scholar on the science of gratitude, “[G]ratitude is more than a feeling. It requires a willingness to recognize (a) that one has been the beneficiary of someone’s kindness, (b) that the benefactor has intentionally provided a benefit, often incurring some personal cost, and (c) that the benefit has value in the eyes of the beneficiary.” Robert A Emmons, Thanks!: How the Science of Gratitude Can Make You Happier (New York, NY: Houghton Mifflin, 2007), 5. Many of the ideas from this section on gratitude come from Alma Acevedo, “Gratitude: An Atheist’s Dissonance,” First Things, published April 14, 2011, accessed November 23, 2019, https://www.firstthings.com/web-exclusives/2011/04/gratitude-an-atheists-dissonance.

[2] For example, when I feel grateful for a friend, this inner gratitude motivates me to display thankfulness for my friend by doing something kind for them (e.g., purchasing them a Starbucks gift card). Emmons and McCullough explain the difference between gratitude and thankfulness in this way: “Being grateful is a state; thanking is an action.” Robert A. Emmons and Michael E. McCullough, The Psychology of Gratitude (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2004), 286.

[3] Can gratefulness be directed toward something material (i.e., something other than a person)? Does it make sense to offer thanks to a material item, such as a coffeemaker? As Emmons notes, “If we subscribe to a standard conception of gratitude, then the answer must be no. My Technivorm Moccamaster coffee brewer does not intentionally provide me with a kindness every morning. But there might be another way to see it. In a blog essay entitled Gratitude as a Measure of Technology, Michael Sacasas suggests that there is nothing bizarre about feeling grateful for technological advances. We could in fact be grateful for material goods…So we can think of gratitude as a measure of what lends genuine value to our lives…So although I am not grateful to my coffeemaker I could legitimately be grateful for it…Thinking about gratitude and technology this way verified what I have believed for some time. We are not grateful for the object itself. Rather, we are grateful for the role the object plays within the complex dynamic of everyday experience. That is what triggers a sense of gratefulness. When it comes to happiness, material goods are not evil in and of themselves. Our ability to feel grateful is not compromised each time we leave home to go shopping or with each click of the ‘add-to-cart’ button. When we are grateful, we can realize that happiness is not contingent on materialistic happenings in our lives but rather comes from our being embedded in caring networks of giving and receiving.” Robert A. Emmons, Gratitude Works!: A 21-Day Program for Creating Emotional Prosperity (San Francisco, CA: Jossey-Bass, 2013), 92-93.

[4] Actually, this is a quote of Dante Rossetti that Chesterton cites. Many people often attribute it to Chesterton, which is why it appears that way in this article, but it is actually a statement by Rossetti.

[5] This was stated by Dawkins in a November 2009 debate at Wellington College in England. The debate was sponsored by a rationalist group known as Intelligence Squared.

[6] Why is a personal God necessary here? Can a person not direct gratitude or offer thanks to an impersonal god (i.e., a force)? Due to the intrinsically personal nature of gratitude and thankfulness, it seems odd to direct these feelings and actions toward anything less than a God who is personal himself. What about other religions, besides Christianity, that claim that God is personal? Although this discussion needs more time and space in order to hash out all of the details, a few brief things need to be mentioned. Because Christianity is the only religion that offers a Trinitarian conception of God, it is the only religion that can claim that God is intrinsically personal. The circulatory character of the triune God (i.e., the doctrine of perichoresis), the mutual giving and receiving of love among the three Persons of the Trinity—Father, Son, and Holy Spirit—serves as a solid ground for maintaining God’s essentially personal nature. Other religions may claim that God is personal, but only in the sense that humans are able to relate to him. Thus, in non-Christian religions, God may be called “personal,” but he is dependent upon humans for his personality and is therefore not intrinsically personal.

[7] Emmons, Thanks!

[8] A special thanks to two of my close friends, Jay Hamilton and Chris Rocco, for proofreading an earlier version of this article and offering helpful feedback. I am so grateful for your friendship!

Editor's Recommendation: Doing What's Right by Gooding and Lennox

/“Navigating the enduring questions about the good and the right, justice and value, scrutinizing their goal, guidance, and ground, David Gooding and John Lennox—with characteristic clarity, courage, and common sense—adroitly unveil both what’s timely and timeless along the moral terrain. The rigorous honesty of their relentless pursuit of a moral account sufficient for both theoretical and practical purposes yields important dividends: insights not just into the human condition and the manifest limitations of materialism, but how morality objectively and robustly construed points beyond itself, intimating of promise and potential we can scarcely imagine.”

More recommendations

Editor's Recommendation: Theodicy of Love by John Peckham

/“A new Peckham book is always an event, and Theodicy of Love does not disappoint. Theologically and philosophically adept, exegetically sound, and analytically rigorous, it offers a rich biblical theodicy in the face of the evidential problem of evil. Peckham’s contribution goes beyond the limitations of a freewill defense and avoids skeptical theism while acknowledging significant epistemic limitations—all while skillfully avoiding an array of potential pitfalls. As fascinating as it is fearless, Peckham’s judicious and perspicacious account assigns primacy to the suffering love of God, who—while operating within certain temporary covenantal strictures—is demonstrating his faithfulness and goodness against cosmic allegations to the contrary. This is an important contribution to theodicy that illuminates a plethora of challenging questions.”

More recommendations

Editor's Recommendation: Stan Key's Journey to Spiritual Wholeness

/Editor's Recommendation: Stan Key's Journey to Spiritual Wholeness

“With his characteristic and signature charm and clarity, power and eminent practicality, preacher and teacher extraordinaire Stan Key (aptly enough) unlocks a vast swath of scripture by adroitly using the lens of the exodus to shed light on how to enter the fullness of God’s promise of spiritual victory—while avoiding notorious pitfalls along the way. At once as uplifting and enchanting as it’s challenging and convicting, Key’s long-awaited book on the geography of salvation is everything I hoped for and more. Rife with trenchant biblical insights, veritably singing with inimitable turns of phrase and dancing with lucid prose, it captures the imagination and invites readers to become fellow pilgrims with the ancient Israelites on a journey saturated with salvific significance today. The result is a treasure-laden pilgrimage readers should not, and with Key’s help definitely will not, ever forget.”

More recommendations

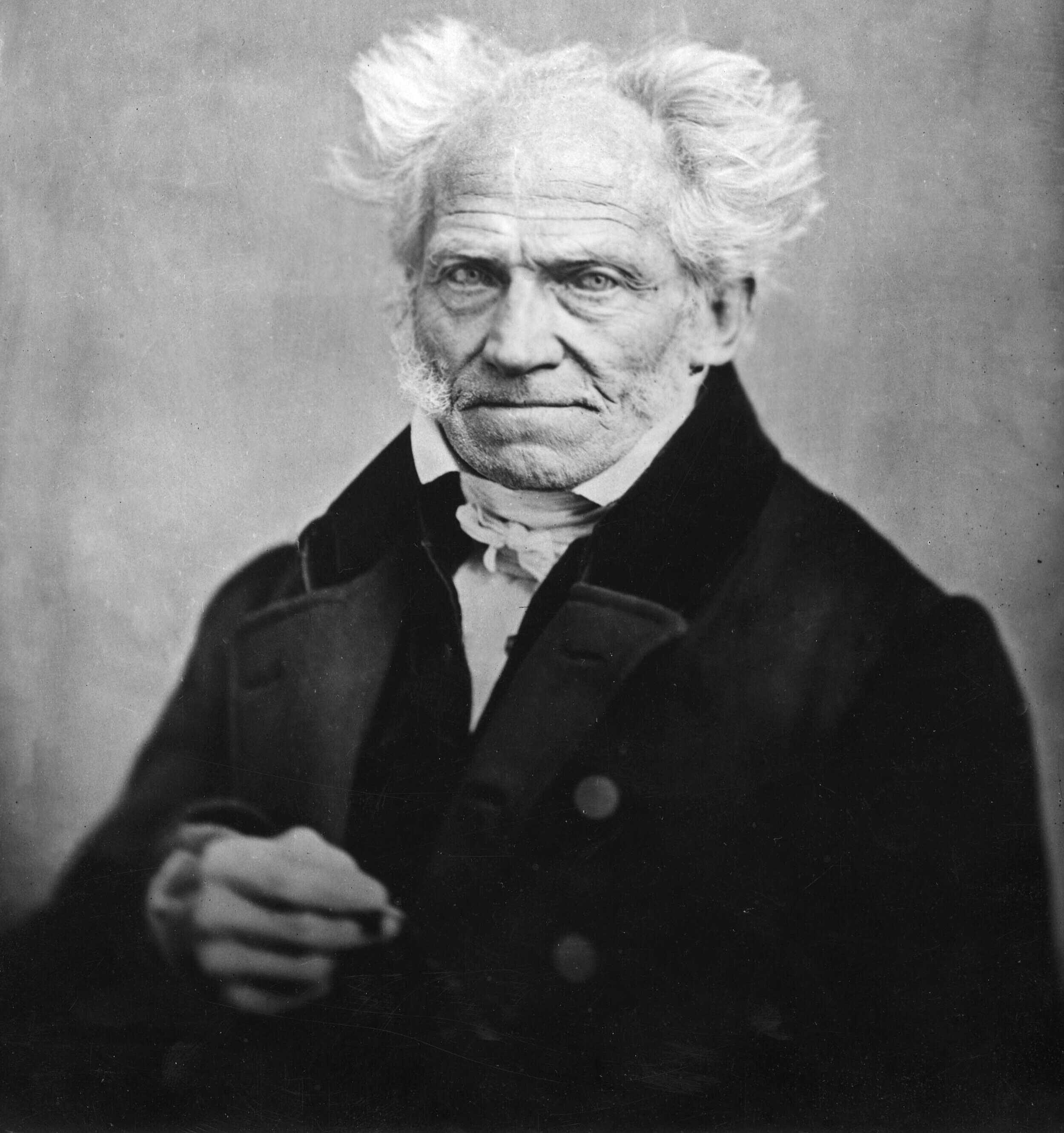

A Few Reflections on Schopenhauer

/A Few Reflections on Schopenhauer

David Baggett

Arthur Schopenhauer’s work had a big influence on Friedrich Nietzsche, especially the latter’s Birth of Tragedy. The similarities between them are numerous, not least the parallel between Schopenhauer’s will and representation, on the one hand, and Nietzsche’s Dionysian and Apollinian, on the other. Both also saw suffering residing at the heart of the human condition, and art as the key to whatever redemption of which we’re capable as human beings. Both came, it would seem, to reject the existence of God; Nietzsche’s bold proclamation of Schopenhauer’s atheism (in The Gay Science) has been critiqued by some for lack of evidence, but it’s generally agreed that many of the implications of Schopenhauer’s depictions of reality are atheistic. At the least God would have been rendered, to paraphrase Laplace, an unnecessary hypothesis.

Much of Schopenhauer’s training in philosophy focused on Plato and Kant in particular, and the latter provided the tools for his metaphysical position, the first of the two big ideas of his magnum opus. Kant’s so-called transcendental idealism wielded a huge influence on Schopenhauer, who was born the same year Kant published his Second Critique. The world and our existence poses a riddle, Schopenhauer thought, in light of the human subjectivity in which we’re trapped. The world as it is in itself is not the world as it appears to us; as a result, everything we experience is mediated by the perceiving subject. We can’t know things as they are in themselves; rather, we can know only our transcendental cognitive framework and the representations it makes possible.

Rather than directing his attention, like Kant did, to what the subject imposes on experience, Schopenhauer instead sought to observe more closely how the subject may be tied intimately with the underlying nature of the world. He looked for an essential homogeneity between the subject and object, and thought the body provided such a link between the inner and outer. The body is not just a spatio-temporal object (something experienced outwardly), but also something we experience inwardly, subjectively, namely, the will. The actions of our bodies are manifestations of our wills.

Schopenhauer even thought that the world as a whole is fundamentally will, offering examples like the following: “The one-year-old bird has no notion of the eggs for which it builds its nest; the young spider has no idea of the prey for which it spins its web; the ant-lion has no notion of the ant for which it digs its cavity for the first time. The larva of the stag-beetle gnaws a hole in the wood, where it will undergo its metamorphosis, twice as large if it is to become a male beetle as if it is to become a female, in order in the former case to have room for the horns, though as yet it has no idea of these. In the actions of such animals the will is obviously at work as in the rest of their activities, but is in blind activity.”

Interestingly, such obviously goal-directed tendencies interwoven throughout nature don’t lead Schopenhauer to affirm teleology in the world, but to deny it. The will in question is characterized as “will without a subject.” Such an interpretation is possible, but it by no means strikes me as obvious or the best explanation. A clear alternative is presupposed in Proverbs 6:6-8: “Go to the ant, you sluggard; consider her ways, and be wise: which having no guide, overseer, or ruler, provides her meat in the summer, and gathers her food in the harvest.” The Bible in fact is replete with lessons about moral or metaphysical truth drawn from garden-variety features and operations of the world. Examples of seemingly teleological instances of the world are an odd choice to drive home a point denying its reality.

Here’s another example Schopenhauer offered: “Let us consider attentively and observe the powerful, irresistible impulse with which masses of water rush downwards, the persistence and determination with which the magnet always turns back to the North Pole, the keen desire with which iron flies to the magnet, the vehemence with which the poles of the electric current strive for reunion, and which, like the vehemence of human desires, is increased by obstacles.” Here he seems to adduce examples of stable natural laws, which, I suppose, can be thought of as evidence of God as a needless hypothesis; but I’m not convinced it’s a good inference. The sort of argument that can be teased out here conspicuously and presciently resembles the suspicion of many today that science and faith are fundamentally at odds, but this seems to be a mistake. Let’s consider just one reason why this is so.

Brian Cutter notes that there are two sides to the human capacity for science: “The first is the fact that the universe is intrinsically intelligible—that nature is structured in a way that admits of rational comprehension…. The second … is that our actual cognitive equipment, such as it is, allows us to discern the broad lineaments of nature, to plumb the deep structure of reality at levels well outside those relevant to life on the savannah. Both of these facts seem much more like what we should expect if Christian theism were true than if naturalism were true. The first fact fits comfortably with the theistic idea that the universe has its source in a Rational Mind, and is really quite surprising on the opposite assumption. And the second fact accords nicely with the Christian doctrine that human beings are made in the image of God, where bearing the image of God has traditionally been supposed to involve, among other things, the possession of an intellectual nature by which we partake in the divine reason.” (See his chapter in Besong and Fuqua’s Faith and Reason.)

On such a view both the existence of stable natural laws and our ability epistemically to access them count evidentially more in favor of theism than atheism, a personal universe rather than an impersonal one. Although an atheist, Schopenhauer may not have altogether been a naturalist, though, because he thought that through art, and music in particular, we can in some sense gain a measure of equanimity in face of the invariable suffering and futility of our lives. Suffering is the norm, he thought, and despite our subjective feelings of willing, we’re not actually free; the sense that we are free is mere appearance.

But rather than leaving us there, Schopenhauer’s second big idea pertained to what we can do in the face of such pessimism. We shouldn’t abandon life itself, but willing in general. Denying the will is the cornerstone of his ethics and aesthetics, and Nietzsche was most struck by Schopenhauer’s aesthetic deliverance from willing. It would seem that Schopenhauer’s notion of will was inextricably tied to notions of futility, of striving, of deficiency, and of suffering. With aesthetic contemplation, he thought, the subject is no longer regarding the object—a beautiful song, for example—in relation to its will. Rather, the object enchants the subject by virtue of its beauty, and as long as it does so the subject’s will is annulled.

In such a situation we find the object beautiful for what it is rather than for its functional capacity, what it does, so willing isn’t needed. The subject thus transcends time and space to realize the eternal realm of a Platonic Idea, and has himself thereby realized his own eternity.

Leaving aside how on earth this shows our “eternity,” two thoughts occur to me here, and with these I’ll end this short analysis. First, his understanding of willing seems flawed, if not idiosyncratic. I don’t feel unfree when I can’t help but recognize objective beauty, or feel the force of a lovely argument whose conclusion is inescapable, or at least eminently reasonable. I rather seem to feel at my most free in such cases. Attentiveness to evidence, apprehension of the lovely, feeling the force of the good—none of these annul my freedom. My freedom most consists in my capacity for just such things!

Just as I don’t see the most salient feature of faith, rightly understood, to be epistemic deficiency, I don’t see the most distinguishing feature of freedom, rightly understood, as existential deficiency. Long before Enlightenment construals of such concepts foisted themselves on us there were traditional understandings of them expressed in quite different terms. The truest freedom, on those more ancient foundations, is to live as we were meant to live; to love the true, the good, and the beautiful because they’re worth loving; freedom from the shackles that would preclude us from becoming fully humanized. So it seems the right goal is not the annulment of our freedom, but its fulfillment, its maximization, which is consistent with constraints to prevent expressions of agency that vitiate rather than conduce to abundant living.

And second, Schopenhauer’s openness to a Platonic paradigm is tantamount to a tacit admission of the inadequacy of naturalism to account for his intuitions here. A personal God strikes me as a better explanation than impersonal Platonic Forms floating in metaphysical limbo; but, while not Christian, Platonism remains eminently congenial to a traditionally theistic understanding of the world. “A Platonic man,” George Mavrodes once wrote, “who sets himself to live in accordance with the Good aligns himself with what is deepest and most basic in existence.”

With his co-author, Jerry Walls, Dr. Baggett authored Good God: The Theistic Foundations of Morality. The book won Christianity Today’s 2012 apologetics book of the year of the award. He developed two subsequent books with Walls. The second book, God and Cosmos: Moral Truth and Human Meaning, critiques naturalistic ethics. The third book, The Moral Argument: A History, chronicles the history of moral arguments for God’s existence. It releases October 1, 2019. Dr. Baggett has also co-edited a collection of essays exploring the philosophy of C.S. Lewis, and edited the third debate between Gary Habermas and Antony Flew on the resurrection of Jesus. Dr. Baggett currently is a professor at the Rawlings School of Divinity in Lynchburg, VA.

Personal Ecclesiastical History (childhood into adolescence): Twilight Musings Autobiography (Part 7)

/Personal Ecclesiastical History (childhood into adolescence): Twilight Musings Autobiography

Elton Higgs

I need to drop back and describe my early religious and social life, from childhood to graduation from high school. The center of my social life has always been connected with my family’s church attendance. We went to church at least three times a week, as did many people of my generation. We had two hours of Sunday School and worship services on the First Day of the week, and then there were regular evening services on Sunday and Wednesday night Prayer Meeting. In addition, my father, as an elder of the South Side Church of Christ in Abilene, TX, often went to “business meetings” on some other night of the week. Once or twice a year, especially in the summer, we would have a week-long “meeting,” an evangelistic effort for which we gathered every night to hear an out-of-town guest speaker. We were supposed to invite our neighbors to attend in the hope that they would “obey the Gospel” by going up to the front of the tent, confessing their faith in Christ, and being baptized. Ideally, they would then become a part of our congregation. Often those who were already Christian would go forward to confess their straying from the Lord. This was called a “restoration” and would be counted along with the baptisms to evaluate the success of our Meeting. During the mornings that week, the guest speaker would conduct classes, mainly for the ladies, since the men were at work.

The South Side congregation was at odds with the other congregations of the Church of Christ in Abilene, and indeed with all of the “mainline” Churches of Christ in the country. We all in common practiced taking Communion every Sunday, did not use instrumental music in worship services, and insisted on immediate baptism as a part of the conversion experience; but we differed in our views of what the Bible taught about the End Times. We, the minority group of the Churches of Christ, were premillennialists, that is, believers that the Second Coming of Christ would usher in a literal thousand-year reign of Christ on earth, along with His faithful followers. Mainline Churches of Christ were vehement rejecters of this doctrine, asserting that the thousand-year reign mentioned in Rev. 20 was figurative, not literal. The family of my best friend in boyhood were members at a mainline Church of Christ only two blocks away from my church. That congregation had been established primarily to combat the heresy of their wayward brothers and sisters down the street. Both their regular preacher and most guest preachers for their week-long evangelistic meetings would target the South Side church in their sermons. My friend often tried to win me away from my error, but I stood firm in my belief.

This rivalry would have been comic if it had not driven such a wedge between congregations which were much more alike than different. However, being a persecuted minority did open us up, years before the mainline began to have this insight, to an understanding of the power and importance of prayer, and of the truth that we are saved by grace and not by works. These two elements in Christian belief and practice would seem to be self-evident from Scripture, but mainline Churches of Christ for many years were quite comfortable combining their emphasis on being the true “New Testament Church” with what amounted to embracing a kind of salvation by works, since their main emphasis was proving that they fulfilled all the requirements set forth in the New Testament to be identified as the True Church. It was a highly rationalistic approach to religion, one that was not sensitive to the “feeling” side of religious experience.

My earliest memory of attending the South Side Church of Christ is of my pre-school Sunday School teacher, Miss Addie Prater—just “Miss Addie” to all the kids. She handed out little picture cards to illustrate the stories she told us. She was a kind woman and was beloved by all. I don’t remember having a personal attachment to any of my other Sunday School teachers, but I felt quite comfortable in my general interactions with adults. I became friends with the other children whose families were regular attenders, and several of these endured through my high school years.

I have memories of the physical layout of the church building. Inside, it was arranged like most Churches of Christ, with a Communion Table in the front center of the auditorium, and a raised podium with a pulpit, and behind that a built-in baptistry, a layout reflecting the church’s emphasis on weekly participation in the Lord’s Supper and baptizing new believers immediately after their confession of faith in Christ The church was heated by floor heaters fueled by natural gas. They had to be lit with a match attached to a long stick. These heaters with their grates received frequent unintended contributions of coins held too loosely in children’s hands. In the summer, cooling had to be supplied by pulling down the tall top windows with a long pole with a hook at the end. Very few churches were air conditioned in those days.

The outside of the building had wide steps leading up to a covered porch supported by three or four tall pillars. On either side of these broad steps, extending out from the porch, were broad concrete “arms” extending horizontally from the top of the steps to the bottom, creating a drop-off at the end of about 4 or 5 feet. It was a wonderful place for show-off boys to jump down from, sometimes pretending to be Hitler jumping off a cliff.

Behind this “new” brick building was a white frame building that was the former church building, which in my young days was used for Sunday School rooms at one end and to house the preacher’s family at the other end. There was no connection between the two buildings, and in rainy weather, one had to make a dash in the open air to get to a Sunday School class.

The big lawn beside the church building, in addition to being used for tent meetings, was also often the site of “dinner on the ground,” that is, a potluck meal. I doubt that even in the early days the food was actually spread out on the ground, like a big picnic, but certainly in the 40s and 50s long tables were set up to hold the food and to seat at least some of the eaters. The home-cooked dishes that were shared on these occasions attracted probably more than did the tent meetings. It was certainly a time of good cheer and fellowship.

This lawn was also a wonderful place to play croquet, a favorite game of the young people’s group during my teen years. The youth group met weekly usually on a Thursday night and was overseen by the preacher and his wife. There were indoor table games as well. Some of them included throwing dice to determine the number of spaces to move on a game board. My father, who was an elder in the church, did not allow dice or playing cards in our home, and he objected to the use of dice in the young people’s games. So our preacher, Karl Kitzmiller (the earliest in my memory), made a spinner that took the place of the dice. Those nights of youth activities were satisfying and full of fun. I was closely bonded with about a half dozen other young people. I still remember the names of some of the people I knew best: Ray Conant, Frances and Wanda Prater, Janice Evans, Barbara Burroughs, Rita Hagar. On Wednesday and Sunday nights after church, we would often go over to a drugstore on Butternut St., about a 15 minute walk, for fountain refreshments. Since I lived within walking distance of the church and the drugstore, I would drop off at home as we walked back. Other preachers I remember from those days were a newly-married couple from Kentucky named Frank and Pat Gill, and a mature man, Jimmy Hardison, who had a daughter named Sylvia, for whom I later, after her family had moved to Louisville, KY, had a brief infatuation. She was the first girl with whom I held hands! But the romance was squashed by her father, who informed me through a letter that she was too young to be courted.

I was an earnest believer in my youth, and I even made occasional forays into personal evangelism. There was a boy 2 or 3 years older than I in the congregation named Jimmie Evans, son of one of the elders. Jimmie was a football player and not by temperament a pious young man like me, so I undertook to bring him to Christ—specifically, to persuade him to be baptized. I would sit with him in a car outside the church between services or after church and preach to him. Amazingly, he finally went forward and was baptized, but it didn’t seem to have much affect on his life, for he became increasingly wilder as time went on. He married right out of high school, and as I remember, the relationship didn’t last. I don’t believe his “conversion” was a very strong validation of my evangelistic methods.

Growing up in the South Side Church of Christ was certainly a spiritually nurturing experience and laid the foundation for my continued church involvement through my life. I learned the value of fellowship with a spiritual family, and much of my identity as a Christian was established in this setting. Sadly, the personal ties made there did not long survive my family’s move away from Abilene, but while they lasted, they helped form my character. I will speak more of my church experience during the next two years in Rule, my high school town, and Stamford, where I lived on my own and had a full-time job during the year between high school and college.

Dr. Elton Higgs was a faculty member in the English department of the University of Michigan-Dearborn from 1965-2001. Having retired from UM-D as Prof. of English in 2001, he now lives with his wife and adult daughter in Jackson, MI.. He has published scholarly articles on Chaucer, Langland, the Pearl Poet, Shakespeare, and Milton. His self-published Collected Poems is online at Lulu.com. He also published a couple dozen short articles in religious journals. (Ed.: Dr. Higgs was the most important mentor during undergrad for the creator of this website, and his influence was inestimable; it's thrilling to welcome this dear friend onboard.)

Ecological Apologetics

/Ecological Apologetics

Caleb Brown

Air travel cultivates appreciation for nature. That I am sitting in a metal tube, bumping elbows with strangers and developing neck strain all fade as I open my window to the blinding beauty outside. Trans-Pacific flights reveal lonely cargo ships, barely visible in the vast blueness that swallows the world. Trans-continental flights survey the barren crags and mesas of the southwestern deserts. From this high up, patterns sifted from the soil by flowing water draw the eye with artistic precision.

Shorter, lower flights allow intimate interaction with aerial terrain. On a hopper from Dallas to Colorado Springs, my propeller plane banked and wove its way through glowering thunder banks. On the way from Charlotte to Gainesville miles of farmland sprouted plumes of smoke that rose and then flattened upon encountering wind. They seemed to be gargantuan, flagged pins on the only real map.

But what did these pins mark? Was the farmers’ attempt to clear their land and produce food harmful as well as efficient and artful? What are the consequences of vaporizing tons of carbon-based plant life through combustion? What, for that matter, is the ecological impact of the flight that enabled me to see what these farmers were doing?

We revel in the beauty of nature, and we must use nature to survive. Both of these truths will not let us leave it alone; they will not let us leave nature natural. Even to experience nature, a pleasure that makes us feel more alive and more human, we must enter it and thereby change it.

There is whimsy and power in human smallness before nature—the gentle curve of a foot-path enhances the grandeur of a mountain. The orange streak of a fragile jetstream lit by a dying sun deepens the purple cast over the Blueridge Mountains. But frail footpaths and ephemeral jetstreams breed the sterile flatness of parking lots and runways.

Perhaps parking lots have their place. But the intuition that the natural world is something good, and therefore is something that must be treated carefully, is undeniable. It strikes us at 32,000 feet and when looking into the eyes of a puppy, when contemplating the cruelty of some humans to that sweet nose and those clumsy paws.

While people differ over where, precisely, this intuition points, and what, exactly, it should lead us to do, members of nearly every demographic and tradition acknowledge that the natural world is good and that our treatment of it is not a neutral matter. Regardless of what is felt to be the right way to treat nature, the conviction that wrong ways exist and have been practiced is nearly universal.

This moral intuition is deep and widespread, but how it meshes with other widespread beliefs is not clear.

If we all got here through the survival of the fittest, why should we be concerned about the wellbeing of non-human species? Certainly, the general wellbeing of the biosphere is important for the wellbeing of humans, but cruelty towards domesticated pets does not impact the survival of humanity. If anything, nurturing these pets diverts resources that could be used by humans. To say that caring for these pets increases our psychological wellbeing is simply to restate in psychological terms our moral intuition that the wellbeing of animals is important.

If mass-extinction events are part and parcel of evolution, then why do we have a moral duty to avoid them? Perhaps, by avoiding mass-extinction events, we are preventing evolutionary progress. How would we feel if primates had thwarted our emergence?

Naturalistic evolutionary attempts to explain our moral intuitions generally attribute them, like everything else about us, to a highly sophisticated sense of self-interest. Our moral intuitions towards nature developed because they are, in the end, best for our own survival, or at least for the propagation of our genes. But even if a sufficiently nuanced evolutionary mechanism could produce these instincts, it cannot explain why it would be wrong for us to act contrary to them. We regularly engage in activities, from eating Oreos to choosing Netflix over exercise, that reduce our health and, through epigenetics, reduce the fitness of our descendants. But if reducing our evolutionary fitness in these ways is not wrong, why would disregarding our survival-driven instincts towards nature be wrong?

It seems that naturalism can only explain the psychological phenomena of our moral intuitions towards the natural world by reducing them to mere instincts. It cannot give these instincts the moral weight we know they possess. Pure naturalism cannot explain our knowledge that the natural world is valuable and that abuse of this world is wrong. It takes something more than naturalism to explain what we know about nature.

But not any type of supernaturalism will do. The trick is to find a way of explaining the value of nature without reducing it, as naturalism does, to something that is unable to ground our moral intuitions. Supernaturalisms that link the spiritual world too closely to the natural world risk reducing the value of the natural world to the worth and power of the spirits that inhabit nature: “The tree is the home of the god, so it is sacred,” or, “I will treat this tree carefully because the spirit that lives in it will make my children sick if I don’t.” Viewpoints like these do not reflect a feeling that the natural world has value in and of itself. Rather, they render it valuable merely by association.

But I think Classical Theism might be a type of supernaturalism that can ground our moral intuitions. Because Classical Theism posits a God who is distinct from nature, it does not reduce the value of nature to that of spirits who inhabit it. Under Classical Theism, to say that the value of the natural world comes from God does not reduce nature’s value to something else, because everything comes from God. God-given value is as inherent, as intrinsic, as real in and of itself as anything in the world. God-given value is not a reality that we can, like our genetic instincts, transcend and ignore.

Many portray our treatment of the natural world as the moral issue of our day. It is certainly one of them. But why is it a moral issue? It seems that naturalism cannot explain the moral significance of nature. Something more is needed. Classical Theism might be this something.

The Psychopath Objection to Divine Command Theory: Another Response to Erik Wielenberg (Part One)

/The Psychopath Objection to Divine Command Theory: Another Response to Erik Wielenberg

Matthew Flannagan

Editor’s note: This article was originally published at MandM.org.nz.

Recently, Erik Wielenberg has developed a novel objection to divine command meta-ethics (DCM). DCM “has the implausible implication that psychopaths have no moral obligations and hence their evil acts, no matter how evil, are morally permissible” (Wielenberg (2008), 1). Wielenberg develops this argument in response to some criticisms of his earlier work. One of the critics he addresses is me. In some forthcoming posts, I will respond to Wielenberg’s arguments. In this post, I will set the scene by explaining the argument and the context in which it occurs. Subsequent posts will offer criticism of the argument

Wielenberg’s New Argument from Psychopathy.

Wielenberg calls his new argument the Psychopathy objection. The Psychopathy objection is the latest move in the contemporary debate between Wielenberg and his critics over the defensibility of divine command meta-ethics. By divine command theory, Wielenberg has in mind the divine command meta-ethics (DCM) defended by Robert Adams (1999) (1979), William Lane Craig (2009), William Alston (1990), Peter Forrest (1989) and C. Stephen Evans (2013). This version of DCM holds that the property of being morally required is identical with the property of being commanded by God.

In previous writings, Wielenberg has pioneered the promulgation objection to divine command meta-ethics. (see Wielenberg (2005), 60–65; Morriston (2009); Wielenberg (2014), 75–80). According to this objection, a divine command theory is problematic because it cannot account for the moral obligations of reasonable unbelievers.

In making this argument, Wielenberg takes for granted the existence of “reasonable non-believers” people whom “—have been brought up in nontheistic religious communities, and quite naturally operate in terms of the assumptions of their own traditions.” Similarly, “many western philosophers, have explicitly considered what is to be said in favor of God’s existence, but have not found it sufficiently persuasive.” Wielenberg assumes many people in these groups are “reasonable non-believers, at least in the sense that their lack of belief cannot be attributed to the violation of any epistemic duty on their part.” (Wielenberg (2018), 77)

Wielenberg argues that if the property of being morally required is identical with the property of being commanded by God, then these people would have no moral obligations. Seeing reasonable non-believers clearly, do have moral obligations it follows that, DCM is false.

Why do reasonable non-believers lack moral obligations, given DCM? Wielenberg cites the following exposition of the problem from Wes Morriston:

Even if he is aware of a “sign” that he somehow manages to interpret as a “command” not to steal, how can he [a reasonable non-believer] be subject to that command if he does not know who issued it, or that it was issued by a competent authority? To appreciate the force of this question, imagine that you have received a note saying, “Let me borrow your car. Leave it unlocked with the key in the ignition, and I will pick it up soon.” If you know that the note is from your spouse, or that it is from a friend to whom you owe a favor, you may perhaps have an obligation to obey this instruction. But if the note is unsigned, the handwriting is unfamiliar, and you have no idea who the author might be, then it is as clear as day that you have no such obligation.

In the same way, it seems that even if our reasonable non-believer gets as far as to interpret one of Adams’ “signs” as conveying the message, “Do not steal”, he will be under no obligation to comply with this instruction unless and until he discovers the divine source of the message. (Morriston (2009), 5-6)

I have responded to Wielenberg both in my book and in a recent article. I argued that Morriston’s argument contains a subtle equivocation. In the first line above, he expresses a disjunction. A person is not subject to a command if he does not know (a) who issued it, or (b) that it has an authoritative source. The example he cites, the case of an anonymous note to borrow one’s car, is a case where neither of these disjuncts holds. The owner of the car knows neither who the author is, nor whether its author has authority. We can illustrate this mistake, by reflecting on examples where, a person does not know who the author of the command is, but does recognize that it has an authoritative source.

Consider two counter-examples I offered, first:

Suppose I am walking down what I take to be a public right of way to Orewa Beach, New Zealand. I come across a locked gate with a sign that says: “private property, do not enter, trespassers will be prosecuted.” In such a situation, I recognize that the owner of the property has written the sign, though I have no idea who the owner is. Does it follow I am not subject to the command? That seems false. To be subject to the command, a person does not need to know who the author of the command is. All they need to know is that the command is authoritative over their conduct. (Flannagan (2017), 348)

A second counter-example I provided was;

Suppose, for example, that an owner of one of the beachfront properties in Orewa puts up a sign that states “private property do not enter, trespassers will be prosecuted” and that John sees the sign and clearly understands what it says. He understands the sign as issuing an imperative to “not enter the property.” John recognizes this imperative is categorical and is telling him to not trespass; he also recognizes this imperative as having authority over his conduct, he also recognizes that he will be blameworthy if he does not comply with this imperative. However, because of a strange metaphysical theory, he does not believe any person issued this imperative and so it is not strictly speaking a command. He thinks it is just a brute fact that this imperative exists. Does this metaphysical idiosyncrasy mean that the command does not apply to him and that he has not heard or received the command the owner issued? That seems to be false. While John does not realize who the source of the command is, he knows enough to know that the imperative the command expresses applies authoritatively to him and that he is accountable to it. (Flannagan (2017), 351)

In the first example, I am aware of the command but do not know who issued it. Despite my ignorance of the source of the command, I know it is authoritative over my conduct, and hence can be said to be subject to it. In the second example, John does not believe he is being commanded. However, he discerns the imperative expressed by the command and is aware both that it authoritatively applies to him and that he is accountable for performing it. A person who doesn’t believe in God can be subject to his commands if he discerns the imperative the command expresses and percieves its authority.

Craig, (2018) Evan’s (2013) and Adams (1999) have raised similar counter-examples. In a dialogue at the University of Purdue between with Wielenberg Craig responded by citing my second example and discussed is subsequently on his podcast. Evan’s gives a similar counter-example. He imagines a person walking on the border between Iraq and Iran, who perceives a sign warning him to stay on the path. Because he is on the border, he does not know whether the Iranian or the Iraqi governments posted the command, yet he knows some government has issued it. (Evans (2013), 113-114) Adam’s argues: “We can suppose it is enough for God’s commanding if God intends the addressee to recognize a requirement as extremely authoritative and as having imperative force. And that recognition can be present in non-theists as well as theists.” (Adams (1999), 268) These examples all suggest that reasonable believers can be “subject to God’s commands” without believing or knowing that God exists.

In his most recent work, Wielenberg (2018) appears to concede the problem. He concludes that a reasonable unbeliever does not need to recognize moral obligations as God’s commands to be subject to them. However, he suggests this response to the promulgation objection raises a deeper worry. Wielenberg suggests that, behind the responses of Evan’s, Adam’s, Craig and myself is a “plausible principle” which he labels R.

(R) God commands person S to do act A only if S is capable of recognizing the requirement to do A as being extremely authoritative and as having imperative force.

R enables the divine command theorist to claim consistently that a reasonable non-believer has moral obligations. However, Wielenberg contends this comes at a cost; this is because when conjoined with DCM, R implies that Psychopath’s lack of moral obligations.

According to Wielenberg “the mainstream view of psychopaths in contemporary psychology and philosophy” which is that lack “conscience and are incapable of grasping the authority and force of moral demands”. Wielenberg states, “According to principle (R) above, since psychopaths cannot grasp morality’s authority and force, God has not issued any commands to them, and so DCT implies that they have no moral obligations” (Wielenberg (2018), 8)

Wielenberg summarises his argument as follows:

The Psychopath Objection to Divine Command Theory

[1] There are some psychopaths who are incapable of grasping the authority and force of moral demands. (empirical premise)

[2] So, there are some psychopaths to whom God has issued no divine commands. (from 1 and R) .

[3] So, if DCT is true, then there are some psychopaths who have no moral obligations. (from 2 and DCT).

[4] But there are no psychopaths who have no moral obligations.

[5.] Therefore, DCT is false. (from 3 and 4)

In the next few posts, I will criticise this argument. In my next post, I will argue that the argument is crucially ambiguous in some of its key terms. In a subsequent post, I will argue that these ambiguities undermine the argument.

Notes:

Adams Robert Divine Command Metaethics Modified Again [Journal] // The Journal of Religious Ethics. – Spring 1979. – 1 : Vol. 7. – pp. 6-79,.

Adams Robert Finite and Infinite Goods: A Framework for Ethics [Book]. – Oxford : Oxford University Press, 1999.

Alston William Some Suggestions for Divine Command Theorists [Book Section] // Christian Theism and the Problems of Philosophy / ed. Beaty Michael. – Notre Dame : Notre Dame University Press, 1990.

Craig William Lane Debate: God & Morality: William Lane Craig vs Erik Wielenberg [Online] // Reasonablefaith.org. – February 23, 2018. – 8 10, 2019. – https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=6iVyVJAMiOY.

Craig William Lane This most Gruesome of Guests [Book Section] // Is Goodness Without God Good Enough? A Debate on Faith, Secularism and Ethics / ed. King Robert K Garcia and Nathan L. – Lanthan: : Rowan and Littlefield Publishers Inc, 2009.

Evans C Stephen God and Moral Obligation [Book]. – Oxford : Oxford University Press, 2013.

Flannagan Matthew Robust Ethics and the Autonomy Thesis [Journal] // Philosophia Christi. – 2017. – 2 : Vol. 17. – pp. 345-362.

Forrest Peter An argument for the Divine Command Theory of Right Action [Journal] // Sophia. – 1989. – 1 : Vol. 28. – pp. 2–19.

Morriston Wes The Moral Obligations of Reasonable Non-Believers: A special problem for divine command meta-ethics [Journal] // International Journal of Philosophy of Religion. – 2009 . – Vol. 65.

Wielenberg Erik Divine command theory and psychopathy [Journal] // Religious Studies. – 2018. – pp. 1-16.

Wielenberg Erik Robust Ethics: The Metaphysics and Epistemology of Godless [Book]. – New York : Oxford University Press, 2014.

Wielenberg Erik Virtue and Value in a Godless Universe [Book]. – Cambridge : Cambridge University Press, 2005

Why We Boldly Go: Moral Truth in Science Fiction

/The unstated assumption of a great deal of science fiction is this: there is a moral world, full of values and duties.

Read MoreEditor's Recomendation: How Reason Can Lead to God

/“A magnificent and prodigious talent as deft in analytic skill as he is adept at uncommon common sense, Joshua Rasmussen has produced a disarming, brilliant, bridge-building book that renders the recondite accessible. It takes readers on a fascinating journey, inviting them to think for themselves, try out his arguments, and come to their own conclusions. He is a remarkable philosopher in the best and old-fashioned sense: respecting his readers; asking vitally important, existentially central questions; rigorously following the evidence where it leads; animated by deep confidence in the revelatory power of reason to show the way. Any genuine seeker of wisdom and truth will find in these pages an eminent kindred spirit and faithful fellow traveler.”

More recommendations

My year in Small-town Rule High School: Twilight Musings Autobiography (Part 6)

/My year in Small-town Rule High School: Twilight Musings Autobiography

Elton D. Higgs

I don’t remember all the details of my family’s move from Abilene to Rule, TX, in the summer of 1955, but I’m sure it must have been once again because of my father’s ill health (cancer) and the need to be near my brother Otho and his family. They had moved to Rule a couple of years earlier to establish an appliance sales and service store, with a jewelry repair service at the back of the store. For me, it was a radical change in culture, and the year I spent there introduced me to experiences that I would never have encountered in Abilene.

Rule was a small town of around 1,500 people, surrounded by small farms. It had a couple of blocks of stores on the main road through town, a cotton gin at the edge of town, and a farming economy that depended on rain and good crops. The high school had about 100 students in it, and the focus was much more on athletics than on academics, as is common in small towns in the South. My graduating senior class had only 21 students, so my previous experience in a “big high school” of several hundred students identified me as a sort of egghead nerd who had never been exposed to the close-to-the-ground life of a farming community.

Athletic games were great social events for the whole town, and boys who played football were minor celebrities. I remember the star of the team was one Sonny Wharton, a good-looking lad who led the pack of boys in my class. Since I had never played football and was not very big, nobody thought it strange that I didn’t volunteer to join the team; but those qualities were no hindrance to my going out briefly for basketball, and then a few weeks of running track. I was pretty much a flop as a basketball player, but I might have had some success at track if I had known how to train. As it was, when I was running my first (and only) 220 yard dash competition, I didn’t pace myself and found my legs giving way, and I skidded several yards on my belly on a cinder track. I had scars for years afterward from that incident. That brought an inglorious end to my athletic endeavors. The burly coach at the school gave my brother Otho a concise assessment of my athletic abilities: “He’s the most uncoordinated 18-year-old I’ve ever seen.” Just as well I had other places to shine.

More to my taste and abilities was participating in the drama team. Since the pool of actors was small, we prepared only a one-act play for the regional drama competition. I learned my lines and was ready to go, but the afternoon of the affair, I was running a fever, and it was all I could do to get through the play, let alone do a quality job. It turned out that I had chicken pox, and I was out of school for a week. Happily, my other drama roles had better results. One of my electives was a Future Farmers of America class (there was a scarcity of alternatives), and one of the activities was a little radio drama on farm safety. Our team went to the state competition and won first place! Who would have thought it? My final thespian venture was the senior play, a farce in which my role as a father involved lathering up my face and pretending to have hydrophobia in order to scare away an unwanted suitor for my “daughter.” The audience loved it!

There was, however, a cruder side to my taking the Future Farmers course. Every class member had to join the school’s FFA chapter, and traditionally that meant going through an initiation of the sort that only high school boys can devise. Like all such unpleasant initiations, it hinged on humiliating and intimidating the new guys, and their showpiece exercise was to have them strip to their birthday suits, get down on all fours, and pretend to be hogs being judged. Each of us had a handler shouting instructions on how best to display our porky selves. The faculty leader was present, but he merely laughed nervously and looked on. I survived the ordeal, but the image of it is indelibly etched on my pictorial memory. At least my enduring without complaint made me accepted by the guys, even if I was basically a city boy.

I held several jobs during that year, the first of which was helping my brother Otho in the installation of appliances and TV antennas. Poor TV reception in Rule meant that many people chose to install an outdoor antenna on their housetop or atop a 60-foot tower with a rotator so that it could be turned 360 degrees to catch the signal from a particular station. Those who couldn’t afford such luxury had to make do with a “rabbit ears” indoor antenna, which usually brought in only a “snowy” picture. I learned some basic electronics in helping install those devices, and that has been a valuable asset ever since. I also clambered on rooftops and climbed up some of those 60-foot towers, which gave me the confidence when I needed to do that for myself later on. (I even installed my own rooftop antenna with a rotator on it at the first house my wife and I bought.)

My work experience with Otho was not without problems. On the lighter side, one time when we were installing a rooftop antenna during the winter, with some snow still on the ground, I was up on the roof following instructions from Otho on the ground. At some point, I started sliding on the wet roof and didn’t stop until I hit a snowdrift down below. When he was assured I wasn’t hurt, Otho burst out laughing, and he enjoyed telling that story for months afterward. He said I just slid down smoothly as if it was a joy ride of some sort. I suspect he wished he had been able to film it.

But another action on my part almost cost him a finger. He had installed a telescoping tower on the back of his pickup to use in raising home towers and accessing them for servicing. While we were in transit, the telescoping tower segments were held in place by a wire wound around the overlapping legs of the segments. The wire had to be taken off, of course, when the tower was ready to be cranked up. One day, the tower seemed to be stuck when I tried to crank it up, and Otho climbed up to see what was wrong. Unfortunately, I had failed to remove the restraining wire, but I kept applying pressure to the crank while Otho was trying to find where the bind was, and the restraining wire snapped and the tower shot up a few feet with great force, catching Otho’s thumb and almost completely severing it. I remember Otho hollering something like, “Elton, you’ve ruined me!” Somehow he managed to keep the thumb from coming completely off, wrapped his bleeding hand with some rags, and drove to the hospital, where they managed to get his thumb sewed back in place. He recovered, but my terrible error rather soured our work relationship for a while.

Another job came from Novis Owsley, the dry goods store owner down the street from Otho’s shop,. They were good friends, so Novis (Mr. Owsley to me, of course) dropped in frequently to the store. One day, he asked me if I would be willing to come in early each morning, before school, and sweep out the store and take out the trash before the store opened for business. I consented, and I spent some good hours listening to popular music on the radio and enjoying being there by myself. I still remember some of the hit tunes of the time that I became familiar with, like “Que Sera, Sera” and “Love and Marriage Go Together Like a Horse and Carriage.” Then, when the fall cotton harvest time came around and the “braceros” (migrant workers from Mexico who picked cotton) would come into the store to buy basic clothes, Mr. Owsley needed someone who could speak enough Spanish to service these workers, and my basic Spanish was sufficient for the job.

So I became a dry goods salesman, along with two classmates who also worked part time. Sammy and Sharon were “an item” at school, so they obviously worked well together, and the three of us became fast friends. Sharon was a sweet Southern girl who showed affection to everybody. Her pet name for me was “El-twan,” and she used it regularly. Sammie was a pleasant but serious young man, and easy to work with. Between us, we sold quite a few clothes for Mr. Owsley. (Some years later, I was surprised to find out that when Sammie and Sharon went away to college, they split up and did not get married as everybody expected.)