Review of Christopher B. Kulp, The Metaphysics of Morality, Part 2

/As I turn now to critically assess Kulp’s thinking, I note that he writes clearly, develops his position in good logical order, and also treats opposing positions briefly but fairly throughout his work. I should point out that my critical assessment comes from a distinctively theistic viewpoint, and that his work is one of several expositions of the ascending viewpoint of moral non-naturalism in the last 20 years or so.[1] Although this book has a lot of the same content as his earlier work, Knowing Moral Truth: A Theory of Metaethics and Moral Knowledge,[2] it develops the metaphysics more thoroughly than the earlier work.

Clearly, the key to understanding Kulp’s metaethical approach is in understanding his starting point for inquiry, namely, tutored, everyday, common sense moral beliefs and commitments. This is where Kulp thinks we must begin because these are foundational to our moral lives.[3] This starting point not only shapes how he proceeds in developing his metaethical account, but also shapes the wider character of that account and how he develops certain key broader themes within his account.

Kulp formulates the bedrock of such everyday common sense moral belief in terms of first-order moral propositions. He does not, for example, appeal to our experience of everyday common sense morality in terms of moral phenomenology, as is common among ethical theorists. His approach is to move from bedrock first-order moral propositions to the nature of morality and its second-order metaphysics.[4] This then is a bottom-up approach that works from bedrock first-order moral propositions to the wider and more encompassing second-order moral metaphysics.

I think that this is a worthwhile and interesting move. I agree with most of his thinking here and also agree with his critique of the various non-realist positions that he engages in a critical way. This thoroughgoing bottom-up approach, however, is not matched by an equally rigorous and logically structured top-down approach in developing the metaphysics of morality. Consequently, key questions over a range of top-down fundamental matters are given no thorough consideration in his analysis.

The most significant of these is a matter that we briefly noted in our previous review which we will now consider in a bit more detail. Recall that in Kulp’s metaphysics the moral domain is ontically distinct; it exists in a mind-independent manner. Recall also that moral properties exist as abstract entities, that they supervene on a base set of physical properties and that they are emergent properties.[5] As Kulp asserts, if there is no physical universe then no morality is possible.[6] What then of the status of the moral domain before the Big Bang?[7] Kulp answers that there was no morality before the Big Bang, nor could there have been since no physical universe existed.

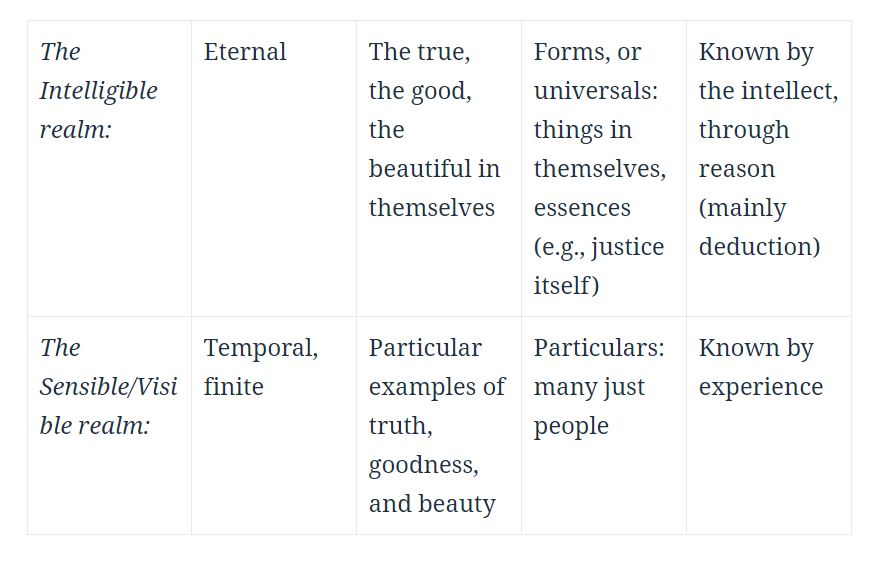

Does this then mean that somehow, at the Big Bang, a mind-independent domain of abstract entities comes into existence, for example, necessary and eternal mathematical truths or mind-independent moral properties, to name just a few of the horde of uninstantiated abstract entities that must exist on Kulp’s Platonic account?

He is also firm on rejecting the idea that our moral beliefs are the result of naturalistic evolutionary forces and rejects evolutionary ethics as strongly physicalistic.[8] This way of formulating the ultimate etiology of the moral is not unusual in the case of the various versions of secular nonnaturalist metaethics.[9] However, these non-naturalist formulations raise a host of vexed questions that need to be answered given that they introduce a number of deep metaphysical challenges.

The fact that Kulp never takes theistic metaethics seriously is telling. The fact that he never works out in a rigorous manner a fully integrated top-down account to balance out his bottom-up account of metaethics is likewise telling. But even his bottom-up approach misses key elements that theism handles quite well. How does a universe such as ours, an intelligible universe, given the kind of moral rational beings that we are, come into being in the first place? Not only does Kulp not attempt to come to terms with such fundamental questions, but his mostly bottom-up oriented approach never forces him to fully confront such fundamental matters.

Moral propositions seem to be the kind of entities that require minded, knowing beings to be the meaningful and distinctive propositions that they are. They are necessarily person related.[10] Does a non-minded, impersonal, morally indifferent universe bring into being non-physical, non-natural, moral properties as abstract entities that are obviously fitted for minded, moral, personal moral beings like us? If this is the case, then how and why is this so? We can see here that the first major top-down challenge for any fully secular, non-theistic account is the existence of the universe itself; this has to be explained.

Then the second fundamental challenge for any impersonalist Platonic non-naturalism is the personal moral beings that we are, coming into being and situated in a vast impersonalist universe that includes an infinite array of uninstantiated, ontically specific, diverse, abstract entities to which we are somehow connected in multiple ways. How does an impersonal universe, truth indifferent, morally indifferent, bring into being the minded, moral persons that morality requires, and how then is abstract, propositional moral truth non-accidentally integrated and matched to moral persons like us? Obviously, some causal story must be true that accounts for the universe in which we live and the moral rational beings that we are.

Kulp offers no such causal account, but only vaguely gestures in this general direction. In this respect his bottom up approach is wholly inadequate. Also, nothing in the causal story can come from the side of abstract entities themselves since, as Kulp acknowledges, and most thinkers concur,[11] abstract entities are to be understood as atemporal, non-spatial, non-causal, non-empirical entities.[12]

We then have here another significant problem for all versions of impersonalist Platonism—the problem of exemplification of properties, and of moral properties in particular. How is it that the universe is made in such a way that abstract properties are exemplified in physical properties in precisely the ways that they are? Mere fluke or grand cosmic coincidence will not suffice here; this amounts to no explanation at all and renders the entire matter deeply problematic and mysterious. Surely this undermines Kulp’s theory.

Additionally, in the case of moral properties, merely invoking something like “emergence” will not suffice.[13] Emergence itself is problematic.[14] Also, the relations of supervenience have been questioned in a similar sort of way as emergence? It is generally understood that supervenience merely states a relation but does not actually explain the stated relations.[15] How did the relations of supervenience come to be the way that they are in the first place and how is it that they continue in just the recurrent ways that they do? How is this relation to be explained?

This matter is particularly acute in the case of Kulp’s moral metaphysic since he rightly rejects all versions of physicalism as well as moral constructivism. Kulp nowhere attempts to come to terms with the vast infinite assortment of ontically diverse abstract entities that must exist on any account like his and how these have come to exist and be integrated and exemplified in the actual world in which we live.[16] Mathematical Platonism is typically seen as the paradigm case of certainty and logical necessity and moral Platonism too easily slides into an unstated assumption that moral propositions are to be conferred a similar sort of certainty and necessity. Clearly, mathematical and moral necessities are different in some important respects.[17] The one is true by logical necessity, the denial of which generates a logical contradiction, while the other is made true as a grounded necessity, the denial of which does not generate a logical contradiction. Grounded necessity is made true given a truth condition relation that makes it true. This involves an asymmetric relation of metaphysical dependence.

In the case of Kulp’s non-naturalist metaethics, moral truth is grounded in complex abstract moral properties and facts. However, the existence of these abstract moral facts themselves, as truth makers, is ultimately left unexplained on Kulp’s account. This is therefore a fundamental metaphysical, ontological gap regarding the nature and origin of these abstracta in his account. Given the above criticisms, once again, the fact that Kulp never takes theistic metaethics seriously is telling.

Theism better explains the universe in which we live, the moral domain and the moral nature of humanity. It better accounts for the moral truth that Kulp wants to argue for. It should be pointed out that Kulp nowhere directly denies theism or argues explicitly against theism, but he clearly proceeds in such a way that God is completely irrelevant to his metaphysics of the moral.

If we take something like Kulp’s bottom up approach and work from the moral nature of humanity, there is much that the theist will agree with in Kulp’s metaethics. Theists will naturally embrace some form of moral realism, some form of moral cognitivism, some form of moral objectivism, some form of moral non-naturalism, perhaps even embracing some form of revised Platonism.[18] In this respect there is wide agreement between theists and secular non-naturalists.

Perhaps the most significant area of agreement between theists and secular non-naturalists is the shared rejection of all forms of naturalism; of physicalism as an adequate account of metaethics. In this regard there is shared consensus between theists and secular non-naturalists that naturalism cannot adequately ground and explain the moral domain and the moral nature of humanity. The theist rightly points out that for humanity to exist the life-friendly universe and all subsequent creative acts for our world to be the kind of world it is must also be accounted for.

To account for the kind of beings that we are, moral-rational beings, theism takes within its creative purview not just humanity and the moral domain, but all the following:

1. The personal creative God that freely creates the contingent universe in which we live; a fine tuned, life permitting universe and world.

2. The personal, minded God that creates complex, specified information.

3. The personal God that creates not only biological information, but information rich biological entities.

4. The personal God that creates sentient biological life and beings.

5. The personal God that creates self-knowing, moral rational beings like us fitted to an intelligible universe.[19]

Moral facts are intrinsically person relatable, that is, person-related facts. This fundamental property of moral facts must be accounted for. It must naturally and fittingly lay into the overall wider metaphysical account of the moral. Impersonalist moral Platonism cannot account for this essential property of moral facts. In a theistic account of Reality personhood is ontologically fundamental to Reality. It does not somehow mysteriously emerge from a finite, contingent, impersonal materialist universe, as must be the case on Kulp’s account. Moral facts thus flow naturally and fittingly, out of a personalist theistic account of Reality.

Since the actual physical universe both has a beginning and is fully contingent, the theist takes issue with Kulp’s affirmation that the physical is both necessary and sufficient for the moral to exist.[20] It is neither. On a theistic account, the living God, a personal, infinite, necessary moral being grounds and manifests the moral domain in and from himself, has freely created humanity to be like himself as regards moral rational being. This God therefore adequately explains the kind of universe in which we live, the moral domain, and the personal dimensions of our existence and the fact that these are integrated and matched from the top down in a necessary sort of way. If the physical universe did not exist the moral domain would still exist–in the living, personal, necessary God. There is thus no need to posit the infinite horde of abstract entities that Kulp’s non-naturalism must posit for his non-physicalist account to succeed.[21]

Theism works equally as a fully integrating top-down explanation of things as well as a comprehensive bottom-up approach that explains the varied particulars of our moral lives; from the Grand Story to the particular story of our everyday, common sense, tutored moral beliefs and commitments.

On the whole, Kulp’s work is commendable and should be read by all who are interested in an accessible exposition of moral non-naturalism. For the theist there is much to agree with in his work. It is clear, well written, and generally well argued. His reviews of the various non-realist metaethical positions are also very useful even though generally brief. But at times Kulp too easily glosses over big issues that he either merely stipulates on, too briefly comments on, or fails to follow through on the logical implications of his own metaphysics. All this taken into consideration, theistic metaethical thinkers should fully engage his work.

[1] For example, see David Enoch, Taking Morality Seriously: A Defense of Robust Realism (Oxford, UK: Oxford University Press, 2013); Russ Shafer-Landau, Moral Realism: A Defence (New York: Clarendon Press; Oxford University Press, 2005); Erik J. Wielenberg, Robust Ethics: The Metaphysics and Epistemology of Godless Normative Realism (Oxford, UK: Oxford University Press, 2014); Michael Huemer, Ethical Intuitionism (New York: Palgrave Macmillan, 2008).

[2] Lexington Books, New York, 2017.

[3] Kulp, Metaphysics of Morality, 6.

[4] Ibid., 8–9.

[5] Ibid., 126.

[6] Ibid., 124.

[7] I fully recognize the problem of using the temporal term “before” in reference to the beginning of the universe. In Perfect Being Theism God is eternal and therefore there is no problem here since God is creator even of our temporal dimensions of time that begin with our physical universe.

[8] Kulp, Metaphysics of Morality, 61.

[9] Each non-naturalist thinker earlier cited formulates his position of the ultimate historical development of the moral in a similar way to Kulp. Each of these thinkers however has attempted a response to the problematic issues raised by evolutionary debunking arguments and other various critiques, whereas Kulp has not. For an overview of debunking arguments, see Guy Kahane, “Evolutionary Debunking Arguments,” Noûs 45, no. 1 (March 2011): 103–125. For an overview of Plantinga’s arguments, see Andrew Moon, “Debunking Morality: Lessons from the EAAN Literature: Debunking Morality,” Pacific Philosophical Quarterly 98 (December 2017): 208–226; Daniel Crow, “A Plantingian Pickle for a Darwinian Dilemma: Evolutionary Arguments Against Atheism and Normative Realism,” Ratio 29, no. 2 (June 2016): 130–148.

[10] Stephen E. Parrish, Atheism?: A Critical Analysis, 2019, 168–171.

[11] Gideon Rosen, “Abstract Objects,” ed. Edward N. Zalta, Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy (Stanford, CA: The Metaphysics Research Lab, Spring 2020); Sam Cowling, Abstract Entities (New Problems of Philosophy) (New York: Routledge, 2017); Bohn, God and Abstract Objects (New York: Cambridge University Press, 2019).

[12] Kulp, Metaphysics of Morality, 157.

[13] Ibid., 126. See for example Olivier Sartenaer, “Sixteen Years Later: Making Sense of Emergence (Again),” Journal for General Philosophy of Science 47, no. 1 (April 2016): 79–103. J.P. Moreland effectively brings out the problems with emergence in his critique of Eric Wielenberg’s “godless normative realism.” See chapter 11 in William Lane Craig, Erik J. Wielenberg, and Adam Lloyd Johnson, A Debate on God and Morality: What Is the Best Account of Objective Moral Values and Duties? (New York: Routledge, 2020).

[14] Pat Lewtas, “The Impossibility of Emergent Conscious Causal Powers,” Australasian Journal of Philosophy 95, no. 3 (July 3, 2017): 475–487. As Lewtas points out, part of the challenge to any view of emergence comes from what is known as “causal closure of the physical.” If a truly emergent property has causal powers emergent from, over and above, the physical properties of the entity in question this is not easily reconciled with causal closure of the physical, i.e. that all causal powers are strictly physical powers that come from within the physical system.

[15] Jaegwon Kim, “Supervenience As a Philosophical Concept.” Metaphilosophy 21, no. 1 & 2 (April 1990): 1–27.

[16] William Lane Craig, God Over All: Divine Aseity and the Challenge of Platonism, First edition. (Oxford, United Kingdom: Oxford University Press, 2016), 18, 41.

[17] For a useful analysis of this see Michael B. Gill, “Morality Is Not Like Mathematics: The Weakness of the Math‐Moral Analogy,” The Southern Journal of Philosophy 57, no. 2 (June 2019): 194–216.

[18] John M. Rist, Real Ethics: Reconsidering the Foundations of Morality (New York: Cambridge University Press, 2002); John M. Rist, Plato’s Moral Realism: The Discovery of the Presuppositions of Ethics (Washington, D.C.: Catholic University of America Press, 2012). Robert Merrihew Adams, Finite and Infinite Goods: A Framework for Ethics (New York: Oxford University Press, 1999). For a good overview of theistic ethics, see David Baggett and Jerry L. Walls, God and Cosmos: Moral Truth and Human Meaning (New York: Oxford University Press, 2016); David Baggett and Jerry L. Walls, Good God: The Theistic Foundations of Morality (New York: Oxford University Press, 2011); David Baggett, The Moral Argument: A History (New York: Oxford University Press, 2019). For another exposition, see John E. Hare, God and Morality: A Philosophical History (Malden, MA: Blackwell Publishing, 2007); John E. Hare, God’s Command (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2015). Note that I include within theistic ethics the natural law tradition as well, see for example Mark C. Murphy, God and Moral Law: On the Theistic Explanation of Morality (New York: Oxford University Press, 2011); Craig A. Boyd, A Shared Morality: A Narrative Defense of Natural Law Ethics (Grand Rapids, MI: Brazos Press, 2007).

[19] A naturalist account of the universe and life has difficulty with all of these necessary precursors to the existence of humanity. See Stephen C. Meyer, The Return of the God Hypothesis: Compelling Scientific Evidence for the Existence of God (New York: HarperOne, 2020).

[20] Kulp, Metaphysics of Morality, 126.

[21] It should be pointed out that Kulp nowhere addresses the view that abstract moral properties might possibly be classed as “naturalistic” yet non-physicalistic. This issue is raised by William J. FitzPatrick, “Ethical Non-Naturalism and Normative Properties,” in New Waves in Metaethics, ed. Michael Brady (London: Palgrave Macmillan UK, 2011), 7–35. Theists have proposed various ways to understand the nature and relation of abstract objects relative to God. See Paul M. Gould, ed., Beyond the Control of God? Six Views on the Problem of God and Abstract Objects, Bloomsbury Studies in Philosophy of Religion (New York: Bloomsbury Publishing, 2014). I espouse a divine conceptualist position wherein these are not autonomous abstract objects but eternal ideal objects in the mind of God. See Stephen E. Parrish, The Knower and the Known: Physicalism, Dualism, and the Nature of Intelligibility (South Bend, Indiana: St. Augustine’s Press, 2013).