Wielenberg on Evolutionary Debunking Arguments

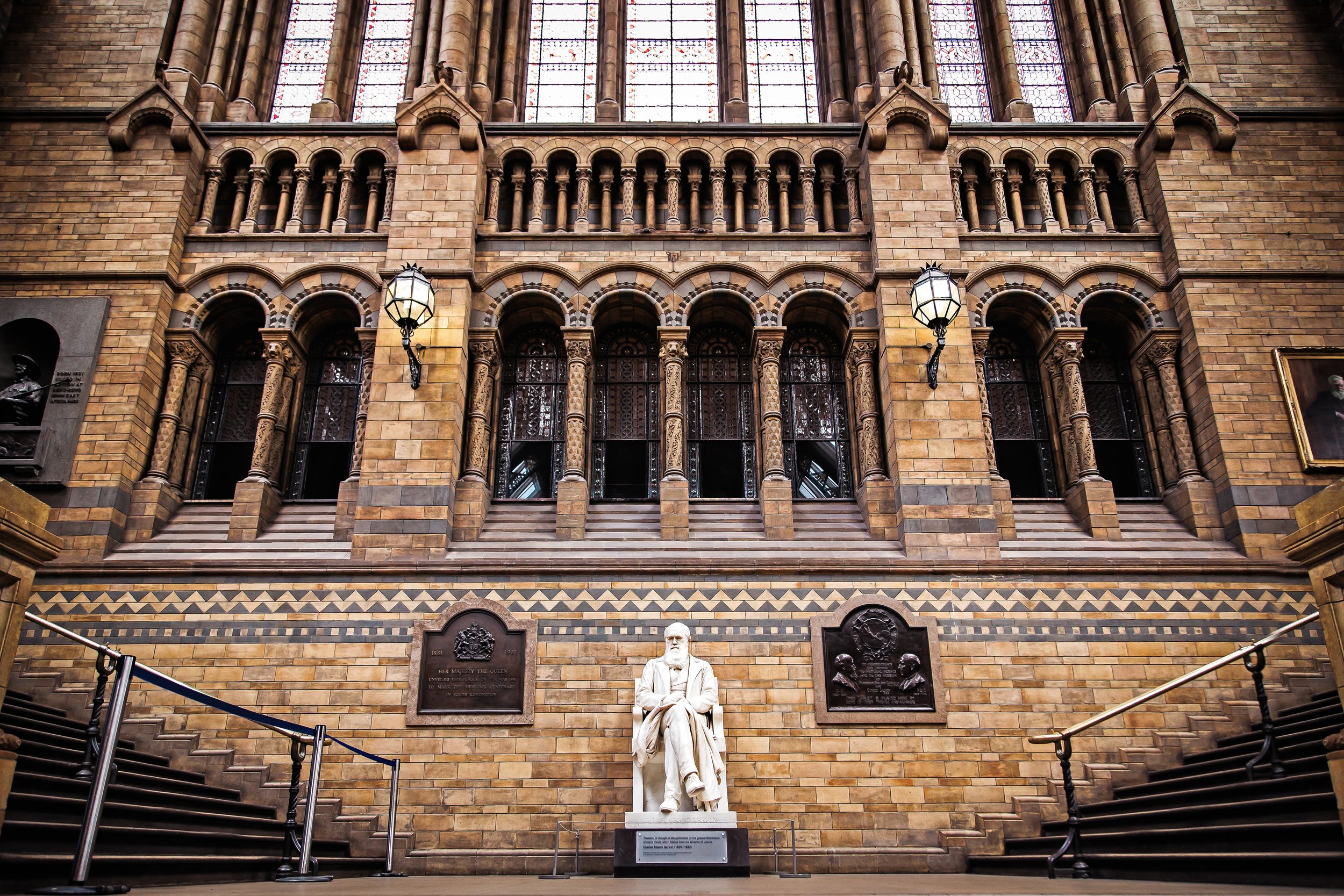

/Photo by Bruno Martins on Unsplash

[Excerpt from a larger essay--my side of a printed debate on God and morality with Louise Antony--forthcoming in a new edition of Michael Peterson and Ray VanArragon, eds., Contemporary Debates in Philosophy of Religion (Blackwell). --MDL]

As a part of a larger project of defending an atheistic accounting of “robust ethics,” Erik Wielenberg has recently taken on such arguments and suggested a model for reconciling an evolutionary account of morality with his view that morality is objective (even “robust”). One assumption of my argument so far has been that unless there is a direct connection between the reproductive advantage of our moral beliefs and their truth--so that their being true is responsible for their being fitness conferring--then we’ve no reason to assume their truth. But as Nagel says, “value realism” is like an unattached spinning wheel. It does no such explanatory work, and so we are left merely with the view that we have the moral beliefs we do because of their reproductive advantage--they have been fobbed off on us by our genes, as Ruse says. Wielenberg instead posits an indirect connection that is routed through a “third factor”[1]-- a set of evolved human cognitive faculties (e.g., reason). It is plausible that certain cognitive faculties have evolved because they confer fitness upon their possessors. Further, there is “wide agreement” that “if rights exist at all, their presence is guaranteed by certain cognitive faculties.”[2] Suppose, then, that there are rights and that such rights are based upon those cognitive faculties. It will follow that any creature with such cognitive faculties possesses rights, and any such creature who exercises those faculties to believe There are rights believes truly. This, of course, is because having the cognitive faculties is both necessary for having the belief and sufficient for having the rights.

In this way, the relevant cognitive faculties are responsible for both moral rights and beliefs about those rights, and so the cognitive faculties explain the correlation between moral rights and beliefs about those rights.[3]

This is a neat way of explaining how evolution might ultimately be responsible for our having true moral beliefs, even if those beliefs are about non-natural truths. Does it succeed?

Wielenberg is entitled to the assumption of rights due to the rhetorical context of his argument. After all, I and others have argued that there would not be moral knowledge even if there were moral truths, and so his strategy--positing some moral truth and determining whether it could be known given the conditions laid down--is the natural way to proceed. And his proposed model is, so far as I can tell, internally consistent. After all, if our cognitive faculties are a product of our evolution, and if having such faculties is sufficient for having rights, then anyone capable of believing that there are rights is in possession of both the faculties and the rights.

But one wonders whether the assumption is safely lifted from the paper and transferred to the world itself. Indeed, there are two assumptions at work: there are rights, and rights are based upon the possession of certain cognitive faculties. Wielenberg cites “wide agreement” regarding the connection between those faculties and the possession of rights. But the entrenched evolutionary skeptic might suggest that our belief in rights is just a part of that fobbed-off illusion. When Bertrand Russell appealed to “wide agreement” regarding certain moral beliefs, George Santayana replied--no doubt with Darwin in mind--that such appeals are little better than “the inevitable and hygienic bias of one race of animals.”[4] Further, given the background assumption of evolutionary naturalism, we might expect that such faculties themselves emerged as an evolutionary solution to the problem of survival and reproduction. As such, they are of instrumental value as a means to such ends, much like opposable thumbs. Can we rest the case for the intrinsic value of persons upon their possession of extrinsically valuable properties? Human rationality is certainly good for humans just as arboreal acrobatic skills are good for rhesus monkeys, but beyond bald assumptions, does Wielenberg’s view provide the conceptual resources for thinking that it is a good in itself as would seem to be required for it to do the work assigned to it?

Wielenberg’s strategy may go some distance towards reducing the improbability of our possessing moral knowledge given the emergence of rational and moral agents who have both rights and a tendency to believe that they do. But the model in itself fails to address a more astonishing cosmic coincidence to which Santayana pointed in his critique of Russell. As an atheist and naturalist, Russell famously said, “Man is the product of causes that had no prevision of the end they were achieving.”[5] The forces of nature are not goal-oriented, and we should not think of the emergence of homo sapiens as the achievement of cosmic purposes. We are here because nature “in her secular hurryings”[6] happened in at least one corner of the universe to throw spinning matter into the right recipe for things such as ourselves to form. But at the same time, Russell defended a view of morality that includes objective and intrinsic values--a form of Platonism not far from Wielenberg’s robust ethics. Santayana argued that these two commitments are mutually at odds. As he saw, Russell’s moral philosophy implied that “In the realm of essences, before anything exists, there are certain essences that have this remarkable property, that they ought to exist, or at least, that, if anything exists, it ought to conform to them.”[7] But Russell’s naturalism--and rejection of cosmic purpose--implies, “What exists…is deaf to this moral emphasis in the eternal; nature exists for no reason.”[8] It would be marvelous indeed if, in the accidental world that Russell described, the very things that ought to exist should have come to be. It would be as though among the eternal verities a special premium had forever been placed upon, say, conscious moral agents, and, despite the countless possibilities, and because of sheer dumb luck, the same had been fashioned and formed of Big Bang debris. Presumably, Beings with cognitive faculties have rights is a necessary truth--if a truth at all--and, as such, it was inscribed in the Platonic empyrean long before the Big Bang. How astonishing it seems that such things with that “remarkable property” of being such that they ought to exist--should have appeared at all when the things responsible for their emergence had no prevision of such an end. Did we win the cosmic lottery? Santayana observed that at least Plato had an explanation for such things because the Good that he conceived was a “power,” influencing the world of people and things so that the course that nature has in fact taken is determined at least in part by moral values.[9] It is for such reasons that Thomas Nagel has posited the idea that “value is not just an accidental side effect of life; rather, there is life because life is a necessary condition of value.”[10] Nagel’s good is a power, unlike Russell’s, and as such it plays a role in explaining the moral shape that the world has taken. But presumably no such moral guidance was at work in Wielenberg’s universe, seeing to it that portions of the material world should be fashioned and formed into moral agents. Yet here we are!

I think this point remains despite Wielenberg’s further ruminations on whether Darwinian Counterfactuals are, in fact, likely or even possible. He suggests that if physical law does not strictly require that emergent moral agents should have developed moral sensibilities something like our own, so that evolution would naturally narrow the range of possible outcomes, it is highly likely--at least “for all we know.” Daniel Dennett has suggested that there may be certain “forced moves” in evolutionary design space. For instance, given locomotion, stereoscopic vision is predictable.[11] Wielenberg seems to be suggesting a forced move of his own. But both moves are forced--if at all--only once certain conditions are in place. Nagel has a relevant observation here on precisely the example Dennett cites.

Once conscious organisms appear on the scene, we can see how it would go. For Example … certain structures necessarily have visual experience, in a sense that inextricably combines phenomenology and capacities for discrimination in the control of action, and that there are no possible structures capable of the same control without the phenomenology. If such structures appeared on the evolutionary menu, they would presumably enhance the fitness of the resulting organisms.... But that would not explain why such structures formed in the first place.[12]

Even if we think it likely that the evolution of moral agents such as ourselves should drop into a predictable groove, we are still left to explain why the natural world should be deeply structured in such a way that its natural processes and algorithms should produce such agents at all. The whole thing is quite wonderful, and without the guidance of God, a Platonic demiurge, or Nagel’s guiding values, it seems an astonishing bit of luck. It adds an additional epicycle of coincidence to the so-called “anthropic coincidences” in that not only have we beat astonishing odds simply by arriving on the scene--because of the mind-boggling improbability that the universe should have permitted and sustained life of any kind--but that it is also the achievement of ends eternally declared to be good and morally desirable by necessarily true but causally impotent moral standards. It is a called shot, but without a Babe Ruth to place it. To base one’s argument on an assumption that defies such odds seems a bit like planning one’s retirement on the assumption that one will win the lottery. One might suggest that Wielenberg help himself to the additional unjustified assumption of Nagel’s causally effective guiding values, for this would fill a void in his view, and anyone with the liberality to grant the one (i.e., rights) is likely to grant the other.

[1] To illustrate, suppose we notice a strong--even exceptionless--correlation between chilly weather and the turning of fall leaves. But suppose we are told that the chill in the air is not the cause of the colorful leaves. But then we consider a third factor--the earth’s tilt from the sun resulting in both less light and colder weather--which is responsible for both the color (due to the light) and the chill.

[2] Wielenberg, p. 145.

[3] Ibid.

[4] Ibid., p. 274.

[5] Bertrand Russell, “A Free Man’s Worship,” in Why I Am Not a Christian and Other Essays (New York: Simon and Schuster, 1957), p. 107.

[6] Ibid., p. 108.

[7] George Santayana, Winds of Doctrine and Platonism and the Spiritual Life (New York: Harper and Brothers, 1957), p. 153.

[8] Ibid., p. 153.

[9] “Plato attributes a single vital direction and a single narrow source to the cosmos. This is what determines and narrows the source of the true good; for the true good is that relevant to nature. Plato would not have been a dogmatic moralist had he not been a theist.” Santayana, Winds of Doctrine, p. 143.

[10] Thomas Nagel, Mind and Consciousness, p. 116.

[11] Daniel Dennett, Darwin’s Dangerous Idea (New York: Simon and Schuster, 1995).

[12] Nagel, Mind and Cosmos, p. 60.

Image: "Darwin" by I. Dolphin. CC License.