In Memory of Storm Baggett (July 8, 2002 – December 26, 2020)

/A memorial to honor Storm Baggett, in remembrance of God’s promise that he is redeeming the cosmos

Read MoreA memorial to honor Storm Baggett, in remembrance of God’s promise that he is redeeming the cosmos

Read More

Editor’s note: R. Scott Smith has graciously allowed us to republish his series, “Making Sense of Morality.” You can find the original post here.

David Hume (d. 1776) also was heavily influenced by mechanical atomism and nominalism. So, no two things are identical; everything is particular. He also was a major British empiricist, such that all knowledge comes by the five senses. Moreover, all that we experience are particular sensory impressions. It is not the case that in daily life we experience objects like tables and cars themselves. Rather, from those sense impressions the mind projects those objects due to custom.

Since we cannot sense empirically anything immaterial, Hume’s views lead to a radical skepticism. We could not know God or the human soul is real. Yet, we also cannot sense the mind, so perhaps we should wonder what it is that does the projecting. Nor can we know custom by the five senses, so we could doubt its reality too.

Applied to morals, they cannot be something immaterial, like many previous ancients and medievals thought, lest we not be able to know them. Additionally, for him, morals are not subject to reason. Reason deals with matters of facts and relations of ideas, he held, but reason cannot tell us what is moral or move us to action. Instead, the prospects of pleasure and pain move us to action, while, in a very move very unlike Aristotle, reason is powerless to do so.

Yet, there is a subordinate role for reason. It can help us figure how to accomplish what we want. Thus, reason is slave of the passions.

There is a major consequence of this view. Consider the sentence, “murder is wrong.” Sentences are empirically knowable. However, many have argued that a proposition is the cognitive content (or meaning) of a sentence. In that case, murder is wrong is a proposition. Now, suppose we deleted that sentence; would we thereby destroy its meaning and that proposition, too? It does not seem so. Moreover, the very same proposition can be expressed in many languages, but that is a characteristic of an immaterial universal, like Plato and Aristotle thought. Such things have an essence, and each universal is one thing, and yet be present in many concrete instances (here, sentences).

This means that for Hume, while sentences are subjects of knowledge, propositions, including moral principles, are not. In these ways, Hume severed facts from morals. That move has been called the fact-value split, which has been with us in the west ever since.

Key for Hume’s morality is the moral sense, or sentiment or feeling. That seems to make an action moral or not. Yet, each feeling is particular and highly individualistic. Also, his ethics seems to be like emotivism, such that moral statements (“murder is wrong”) would be just emotive utterances (e.g., “ugh, murder!”). But, if so, they cannot be true or false, for they are non-cognitive. They are just expressions of feelings.

With this highly individualistic emphasis, Hume’s ethics could seem to lead to anarchy. Yet, he also was quite high on keeping the status quo. To do that, he also held a high place for social order and utility.

What then should we make of his ethics, particularly in terms of preserving our core morals? Clearly, the idea that morality is just a matter of each person’s own feelings is very much alive now, especially in the U.S. Still, by gutting morals of their cognitive content, he also removed their normativity. So, murder’s and rape’s wrongness, and justice’s and love’s goodness, would be undermined. All we would have would be expressions of feelings. But those are just descriptive, not normative.

Moreover, on his view, why should a sociopath be prevented from acting on his or her passions? Without any cognitive content to morals, we lose all ability to know what actions we should, or shouldn’t, do. Yet, from our core morals, we know that that is not so. Further, his appeal to social order seems ad hoc, given the rest of his theory.

Next, we will look at Immanuel Kant’s ethics.

Hume, An Enquiry Concerning the Principles of Morals, and A Treatise of Human Nature R. Scott Smith, In Search of Moral Knowledge, ch. 4

R. Scott Smith is a Christian philosopher and apologist, with special interests in ethics, knowledge, and seeing the body of Christ live in the fullness of the Spirit and truth.

Editor’s note: R. Scott Smith has graciously allowed us to republish his series, “Making Sense of Morality.” You can find the original post here.

As key thinker behind the shifts in the Scientific Revolution, Thomas Hobbes embraced mechanical atomism and nominalism. A major focus on empirical knowledge also ensued. Not only was his book, Leviathan (1651), shaped by these factors, he also was influenced by the English civil war between Charles I and Parliament.

For Hobbes, humans are just material beings. Fittingly, he thought external objects caused motions in us, and these motions included things like desires and aversions, thoughts, beliefs, and more. An external object causes a motion in us toward it. Such a motion is a desire for something, which he claimed is good. Similarly, aversions were caused by external objects, but they caused motions away from them, which he said were bad.

He also defined the good in terms of self-interest (ethical egoism), which we ought to pursue. Further, we do in fact act in our self-interest (psychological egoism). But, self-interest is not necessarily identical with pleasure.

Hobbes posited that we have a restless desire for power. If people desire the same object, there is conflict. If everyone pursues his or her self-interest, there will be a persistent fear of violence, which he called a state of war.

Now, unlike the views we just surveyed, on materialism, there are no transcendent, objectively real morals. So, acts are not wrong until a humanly-made law forbids it. To preserve a peoples’ safety, they need to form a social contract with a sovereign ruler, or Leviathan, to keep the peace and defend their rights which he would promulgate. The Leviathan would exercise all functions (executive, legislative, and judicial) of government. While this could be a tyrant, Hobbes thought that the sovereign’s body is composed of the people he rules. Since he too would act egoistically, he would act in the peoples’ best interests.

Only the Leviathan gives rights; there are no natural rights, except the right of nature (to preserve one’s own life). Nor would any other rights be inalienable, for they are given by government. While Hobbes spoke of “natural laws,” they were not objectively real, immaterial laws that we could know by reason. Rather, they were maxims for our lives.

By way of assessment, there are several issues with his ethics. First, there is no room for moral reformers. Whatever the sovereign decrees is law and therefore moral, unless of course he violates peoples’ own right of nature.

Second, Hobbes doesn’t seem to anticipate any problem with material beings making choices, like ceding their rights and forming a social contract. Nor does he see an issue with making rational decisions. Yet, if we are but mechanisms, and even our desires (or aversions), let alone other “mental” states, are caused by the motions external, material objects produce in us, then it seems there is no room for free will. How then can we be ethically responsible for our actions? Likewise, how can we make rational choices to believe the truth?

Third, can his views preserve our core morals: murder and rape are wrong, and justice and love are good? I don’t think so. In a completely material world, things can be exhausted descriptively. But while careful descriptions of the various factors involved in ethical decision-making is important, ethics involves what we ought, or ought not, do or be. Ethics is a normative discipline, but Hobbes’s materialism seems unable to account for that.

Finally, consider what is good (or bad) in terms of Hobbesian motions. Murder’s or rape’s wrongness would be based on the motions an object (presumably the intended victim) caused in the perpetrator. According to Hobbes, something morally wrong would be a motion away from something. But that is not what happens in acts of murder or rape; the perpetrator moves toward the victim, which, on Hobbes’s view, would be good. Moreover, it seems the victim is the one to be blamed, for that person caused the motions in the perpetrator! Further, justice is more than motions; both a just and an unjust act could involve motions toward someone, or something. So, tellingly, it seems Hobbes’s theory cannot preserve our core morals.

Hobbes, Leviathan

R. Scott Smith, In Search of Moral Knowledge, ch. 4

“Glory to God in the highest heaven, and on earth peace to those on whom his favor rests”

Trip back to the 1960’s: I am living without peace; so is much of the country. The inner turmoil convulsing in me mirrors the outer world; it is tearing at the inner seams. Everything is topsy-turvy, upside-down, and wrong-side up. Enduring principles, paragons, and precepts are disputed. Is there no fixed point? Moreover, America and the USSR are locked in a ‘Cold War’ from Berlin to Viet Nam; blacks struggle for equality; cities burn; and revolutionaries clash with the status-quo; even in my own family conflict surges: my parents, when not shouting at each other, are yelling at me. The year is 1968 - it seems like 2020. I have no peace.

The waring polarities - protester-establishment; male-female; black-white; young-old - converge with my inner turmoil. People in the streets cry, ‘Peace, Peace’, but there is no peace.

In 1969 at nineteen, a watershed moment occurs: my eyes are opened. I see my problem - each person’s problem - I am estranged from God. “We were enemies” says the apostle Paul. I am God’s rival every bit as much as Winston Churchill was Lady Astor’s. She said to him, “If I were your wife, I’d put poison in your tea.” He replied, “Madam, if I were your husband, I’d drink it.”

I deny it. Me, an enemy of God? Ridiculous. What? Am I not living as though I am the King of me? A kingdom cannot have two kings. Philosopher Bertrand Russell quipped, “Every man would like to be God if it were possible; some few find it difficult to admit the impossibility.”

Has not God declared, ‘I am God and there is no other”? I am living de facto as God. This is a recipe for war. I own up to it: I am trying to be king in God’s country. I am in a state of enmity with God.

Then I learn God did something to break the impasse: he sued for peace. “While we were still sinners Christ died for us,” says the apostle Paul. God comes at Christmas to give us Easter. He comes in the flesh to bring peace; He comes to offer friendly relations with himself by dying an atoning death on a cross: “Peace on earth, mercy mild, God and sinners reconciled!” Abraham Lincoln said, “Am I not destroying my enemies when I make friends of them?” God exchanges a “falling out” for friendship. “God was pleased to reconcile to Himself all things” - even me - declares the apostle Paul. Jesus made friends with this enemy; his truce with me is everything. Accepting this Prince of Peace has imparted peace that runs deeper than tempests. Since then, my heart gladly exclaims, “Hail the heaven-born Prince of Peace!”

Etched in my mind this Christmas is the 1972 iconic photograph of the naked nine year old girl, Kim Phuc Phan Thi, fleeing down a Viet Nam roadway shrieking in pain and fear with an ominous, dark, billowing napalm cloud behind her. Scarred physically and emotionally from burns over her body, Phan prays to the god of Cao Dai for healing and peace. There is no answer. Either he is not interested, or not there. Later, she is inside Saigon’s central library thumbing through religious books on Baha’i, Buddhism, Hinduism, Islam, and Cao Dai…then she picks up the New Testament. She reads through the Gospels. She is struck by Jesus. He claims to be “the way, and the truth and the life.” He is tortured for his claim. The more she reads the more she is convinced he would not suffer such things if he were not God. As she continues to read the New Testament, she finds Jesus’ claim authentic.

On Christmas Eve 1982, she attends worship at a small church in Saigon - just minutes away from where she was bombed. The pastor speaks of Christmas gifts but especially of the gift of Jesus Christ. “How desperately I needed peace,” Phan says. “I had so much hatred in my heart…I wanted to let go of all the pain…I wanted this Jesus”. On the night before the birth of our Lord, she stands up, steps into the aisle, and strides to the front of the sanctuary. She says ‘Yes’ to him, inviting “Jesus into my heart”.

When she awakes on Christmas morn, Phan says, “I was finally at peace”. A half century after running down the Saigon road screaming in pain and fear, she celebrates the freedom and peace Jesus Christ gives. Having been through unspeakable horrors, she realizes there is nothing greater than the love of our blessed Savior. Fifty years later, this writer, though his circumstances are different from Phan’s, rejoices in the same peace of the Prince of Peace, proclaiming,

“Glory be to God on high, and peace on earth, descend; God comes down, he bows the sky, and shows himself our friend.”

Tom is currently a retired Elder in the Virginia Annual Conference. He has pastored churches in Virginia, California and England. Studying John Wesley’s theology, he received his Ph.D. and M.A. degrees from the University of Bristol, Bristol, England and his Master of Divinity degree from Asbury Theological Seminary. While a student, he and his wife Pam lived in John Wesley’s Chapel “The New Room”, Bristol, England, the first established Methodist preaching house. Tom was a faculty member of Asbury Theological Seminary. He has contributed articles to Methodist History and the Wesleyan Theological Journal. He and his wife have two children, daughter Karissa, who is an attorney in Richmond, Virginia, and, John, who is a recent graduate of Regent University. Being a part of the development of their grandson Beau is a rich reward. Tom enjoys a good book by a crackling fire with an English cup of tea. His life text is, ‘Jesus, confirm my heart’s desire, to work and speak and think for thee’

Editor’s note: R. Scott Smith has graciously allowed us to republish his series, “Making Sense of Morality.” You can find the original post here.

Like we have seen with Thomas Aquinas, the Scholastics’ Aristotelianism in the Middle Ages stressed metaphysics, especially real, immaterial, and universal qualities. This applied not only to human nature, but also to virtues and moral principles. As universals, many particular, individual humans can exemplify the very same quality (a one-in-many).

With this stress upon universals and their essential natures, Aristotelianism lent itself to a more a priori (in-principle), deductive approach to science. But, this position started to shift with William of Ockham (d. 1347). Ockham rejected universals, and in its place embraced nominalism. Unlike universals, nominalism maintains that everything is particular. For instance, while we may speak of the virtue of justice, each instance of justice is particular, and they do not share literally the identical quality. Now, Plato’s universals, which held that universals (or forms) themselves are not located in space and time, and this would fit with their being immaterial. But, nominalism rejects that view. On it, all particulars are located in space and time. That implies that they are material and sense perceptible.

About two and one-half centuries later, two key philosophers in the early modern period, Pierre Gassendi (d. 1655) and Thomas Hobbes (d. 1679), embraced nominalism. Gassendi also revived Democritus’ atomism, on which the material world is made up of atoms in the void. Hobbes and Gassendi also adopted a mechanical view of the universe: it is a large-scale machine, and so are the things within it. These views shift away the reality of immaterial things and embrace instead materialism.

These philosophers helped set a basis for natural philosophy (science) in the emerging modern era. Johannes Kepler (d. 1630) adopted the mechanical view, and scientists such as Francis Bacon (d. 1626), Galileo Galilei (d. 1642), Robert Boyle (d. 1691), and Isaac Newton (d. 1727) endorsed mechanical atomism. Yet, there was a key difference in the atomism of this period from that of Democritus. Probably due to the influence of Christianity in Europe in this time, people tended to think that atomism applied only to the material realm, but not the spiritual one. They still had room for the reality of minds, souls, angels, and God.

The qualities of matter (e.g., size, shape, quantity, and location) were thought to be primary qualities. In contrast, the qualities of the spiritual realm (e.g., colors, tastes, or odors) were considered to be secondary qualities. Secondary qualities either were subjective qualities in the mind of an observer, or words that people used. In other words, they did not exist objectively.

Here, we must note something of immense importance. It was not scientific discoveries which drove this shift away from universals and a dualistic view of reality. Instead, it largely was due to the adoption of philosophical theories, namely, nominalism and mechanical atomism.

What is the significance of this shift? Boyle illustrates it well; he thought secondary qualities and Aristotelian universals were unintelligible due to what he conceived to be real in the material world. Of course, that conception was informed deeply by mechanical atomism and nominalism.

Instead of the Aristotelian paradigm, a new scientific methodology developed. It stressed empirical observation of particular, material things. On the new paradigm, things did not have essences that necessitated certain causal effects. Instead, the new scientific methodology focused on contingent causes and induction. While Aristotelianism had encountered empirical problems (e.g., the discovery of new species of which he did not know), the new methodology provided an advancement. Instead of relying overly on metaphysical theories, it emphasized the importance of empirical observation of the world.

These shifts in the nature of what is real, and how we know it, became deeply entrenched, and they affected ethics too. Next, I will look at Hobbes’s ethics. The key question will be: can his ethics preserve core morals?

Alan Chalmers, “Atomism from the 17th to the 20th Century,” Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy. https://plato.stanford.edu/entries/atomism-modern/

Eva Del Soldato, “Natural Philosophy in the Renaissance,” Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy. https://plato.stanford.edu/entries/natphil-ren/.

Galileo Galilei, Il Saggiatore [The Assayer], in Discoveries and Opinions of Galileo. https://www.princeton.edu/~hos/h291/assayer.htm#_ftn19. Jürgen Klein, “Francis Bacon.” https://plato.stanford.edu/entries/francis-bacon/

R. Scott Smith is a Christian philosopher and apologist, with special interests in ethics, knowledge, and seeing the body of Christ live in the fullness of the Spirit and truth.

What logical reason is there that God is good? In this episode, I Interview David Baggett. Dr. Baggett author of Good God: The Theistic Foundations of Morality. The book won Christianity Today’s 2012 apologetics book of the year of the award. He published a sequel with Walls that critiques naturalistic ethics, God and Cosmos: Moral Truth and Human Meaning. A third book in the series, The Moral Argument: A History, chronicles the history of moral arguments for God’s existence. Dr. Baggett has also co-edited a collection of essays exploring the philosophy of C.S. Lewis, and edited the third debate between Gary Habermas and Antony Flew on the resurrection of Jesus. Dr. Baggett currently is a professor at Houston Baptist University

Editor’s note: R. Scott Smith has graciously allowed us to republish his series, “Making Sense of Morality.” You can find the original post here.

In this period between the ancient Greeks and the Scientific Revolution, there also was the rise of Islamic ethics. In Islam’s “classical” period, several schools of thought developed, which cover an epistemological spectrum of how we know what is right. At one end were the rationalists, including Avicenna and Averroes. In their view, moral truths exist objectively, even apart from Allah. Reason can discover moral truths, which does not conflict with revelation.

Next along this spectrum were the Mutazalites. For them, too, morals exist objectively. We can know them from the Qur’an, the Traditions of Mohammed, or independent reason. Some thought we could know morals independently of revelation. Further, they reasoned that theistic voluntarism (morality is based solely on Allah’s will) could lead to some immoral conclusions.

In response, Sunni theologians (or traditionalists) held the sovereignty of Allah as their supreme principle. They disputed the Mutazalites’ view that there are objectively real moral principles that even Allah follows. Such truths would exist independently of Allah’s sovereign will. In effect, independent reason limited Allah’s power, and objective morals had to be rejected. For Ashari, morals are what Allah commands, which ultimately we know only from revelation.

For traditionalists, ethics is one of action (doing Allah’s will). While there has been room for virtue in Islamic ethics, for traditionalists, virtues are not ends in themselves. Instead, the beginning of Islamic ethics is submission, and the end is obedience. Since the traditionalist view realizes both the fundamental point of Allah’s omnipotence, as well as revelation as the basis for knowing what is right, it is easy to see how this view came to dominate.

So, can the traditionalist view preserve these core morals? Yes, but only if Allah so wills that they are valid. But, there are no limits on Allah’s sovereignty, as is the case with the Judeo-Christian God’s character, so conceivably Allah could will they are invalid, and we would have no basis for complaint.

George F. Hourani, Reason and Tradition in Islamic Ethics

R. Scott Smith, In Search of Moral Knowledge, ch. 3

R. Scott Smith is a Christian philosopher and apologist, with special interests in ethics, knowledge, and seeing the body of Christ live in the fullness of the Spirit and truth.

Editor’s note: R. Scott Smith has graciously allowed us to republish his series, “Making Sense of Morality.” You can find the original post here.

To begin our historical tour, I will start with the ancient Greeks. I will focus on Plato and Aristotle, who still much influence on western ethics.

For Plato, morals are not human products. Instead, they exist objectively in the intelligible realm, which includes the forms. A form is a universal that itself is not located in space and time (it is metaphysically abstract). A universal is one thing, yet it can have many instances in the visible, sensible realm. For example, justice is a universal, and there can be many just people. The identical quality, justice, can be found in many instances.

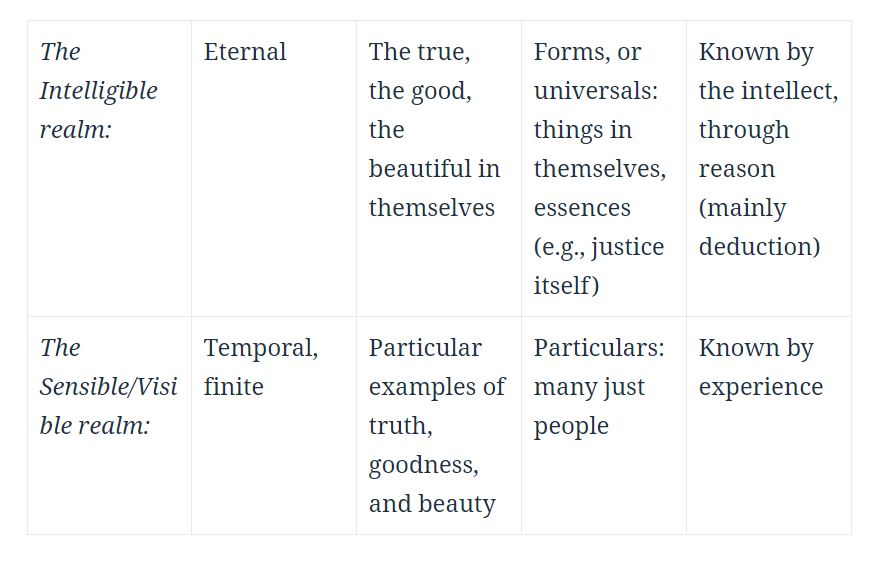

A comparison of these two realms:

Plato’s Two Realms

Justice can be instanced in a human being because humans are a body-soul duality, and the soul is their essential nature that defines them as the kind of thing they are. All humans should be just, and to reach their true goal, or telos, they need a proper balance of the good, the true, and the beautiful.

Yet, it is hard to reach the telos, for the process of education in the knowledge of the good is very difficult. His “cave” illustration shows that only a few people leave the “shadows,” a place of illusions which they mistake for reality. Instead, only a few strive toward the true light outside the cave and acquire knowledge of the forms.

In this, Plato questionably assumes all people want to be virtuous. All they need is education and effort. Furthermore, though he realizes people should be virtuous, he seems to lack a “connection” between the moral forms and human nature. Why is justice appropriate for our souls?

Today, it is hard for many even to conceive that there could be immaterial and objectively real entities. Still, can Plato’s view sustain the four core morals? It seems it can; the virtues of love and justice, as well as the principles that we should not murder or rape, would be universals that are normative for all. Moreover, we know these morals by reason, which fits with our intuitive knowledge of their validity.

For Aristotle, there is a deep unity between the body and the soul. The body is appropriate for humans due to the kind of thing they are (i.e., our essence). Similarly, the cardinal virtues (prudence, temperance, justice, and courage) are appropriate for humans due to their soul’s nature. As one’s essence, the soul enables a person to grow and change and yet remain the same person. That is, one’s personal identity is constituted by one’s set of essential properties and capacities (even for virtues), which do not change. If people changed in some way essential to them, they’d no longer exist! Yet, they can undergo other kinds of changes, like the development of the virtues, and still be the same individuals.

Aristotle’s ethics is practical, seeking how to achieve the function of a human being, which is to guide one’s actions by reason. The virtues are developed by habituation and training. This involves being apprenticed to someone who has the virtues. Moreover, virtues are a mean between two extremes. For instance, courage is a mean between cowardliness (a vice of deficiency) and rashness (the vice of excessiveness). Moreover, like Plato, the good is found in community; Aristotle would not support the western, autonomous individual.

Like Plato, Aristotle believed in universals, though they always had to be instanced in particulars. Still, immaterial, objectively real universals exist, which rubs against today’s common belief that humans are just physical things. Moreover, he was pretty confident in human abilities to use our reason and know universal truths, as well as in our abilities to be virtuous by habituation. Even so, like Plato, it seems his views can preserve the four core morals and our knowledge thereof. Of course, we will have to see later if it is reasonable to believe there are real, immaterial universals.

Aristotle, Nichomachean Ethics

Plato, The Republic, Books, 4, 6, 7, & 10

R. Scott Smith, In Search of Moral Knowledge, ch. 2

R. Scott Smith is a Christian philosopher and apologist, with special interests in ethics, knowledge, and seeing the body of Christ live in the fullness of the Spirit and truth.

Buffy had been losing weight for a few weeks, but the procedure was supposed to be routine. Still, there we sat in the vet’s office listening to the doctor explain that our kitty just wasn’t recovering from her biopsy.

Her blood pressure and temperature were dangerously low, and our normally energetic, friendly cat could barely lift her head and seemed hardly even to recognize us. Her eyes were glazed over, her breathing labored.

My husband and I sat in the room numb, struggling to grasp how it could be that our ten-year-old, always healthy pet was now lying listless in an incubator as the vet did all she could to stimulate the healing process.

A few of the doctor’s words penetrated our mental fog, but they only added to our confusion: “We’re not ready to give up on Buffy yet,” “Let’s keep her in the emergency clinic overnight,” “Do you want to add a DNR?” We had no framework into which we could fit these statements, no sense of how this happened, let alone how to respond.

Buffy’s death followed soon after, and it was a devastating punch to the gut—no less because it came a week before our cross-country move. We had picked the house in Texas with Buffy in mind and had imagined her there, sitting next to David in his office while he worked as she so faithfully did in Lynchburg, hanging out with us while we watched TV, running around playing with the laser light. But now she wouldn’t be coming with us. It was a hard realization to take. Grief mingled with anger came quick, but the demands of the moment left little space for mourning.

Inside the house I was packing boxes while outside our son was digging Buffy a grave, a grave we would have to leave behind. The rapid approach of our moving day meant no time for a memorial, no time to be still and simply reflect on this precious cat’s life. I felt an impulse to rage against the meaninglessness of it all, but had no energy or mental space to generate the emotions.

Buffy’s death—so unexpected, so wrong, and yet so inescapable—somehow symbolized all I felt about this summer’s transition. There would be promising possibilities waiting for us in our new location and new positions, I knew, but what loomed larger for me at that moment was all I stood to lose with the move, and Buffy’s death underscored that loss, crystalizing and compounding it.

The comfort of home, the familiarity of Lynchburg, the intimate acquaintance with my late institution’s practices and policies: these would soon be no more. Harder still was moving 1,200 miles from my family and son and leaving behind friends and beloved colleagues. And all of this during a pandemic. This transition has been one of the most difficult experiences I’ve had to endure—with its logistical challenges, financial burdens, and emotional tolls.

Although I know on one level that the conditions at our past school would have made staying there more challenging in the long run, my longing for comfort and my visceral resistance to the loss entailed by our fresh start persisted and sometimes manifested in anger. I was angry that my many prayers for spiritual renewal at Liberty returned unanswered and seemingly unheard, that conditions worsened even.

I was angry that God’s answer to my pleas for deliverance involved so much loss and pain. And I was angry that those responsible for the unbearable conditions were either unaware of or unmoved by the pain they caused. Like Buffy’s death, it all just felt so wrong. It was hard to square with my vision of God, the one who cares and comforts, who sets things right. Why had he refused to set things right? Or, rather, why was the remedy he offered, this escape, so painful?

Over the summer, I wrestled with the paradox of trusting the redemption of my pain and loss—of Buffy, of our home in Lynchburg—to the same God who allowed that loss in the first place.

I know the biblical promises of the resurrection. I know that they apply not merely to the physical body but also to the cosmos. “Behold, I make all things new,” Jesus says in Revelation. It’s a beautiful promise—life-giving in every sense of the phrase. But as much as I’ve professed my embrace of those truths, even earlier this summer in writing about the pandemic, Buffy’s loss conjoined with our move tested that faith. I am only now starting to believe that that testing strengthened it.

The pain I endured through Buffy’s loss and this transition has pushed me further in my recognition of how little I know of God’s redemption of the world or even of what in the world God has redeemed. Day by day I had to lean on God to provide the strength I lacked, the comfort for my hurts, and the hope to overcome my fears. It was a sobering time, too, as it forced me to confront my own self-entitlement, pride, and complacency.

I longed for God to prevent Buffy’s death and to accommodate my desire to remain in place. Truth is, Christianity teaches that real victory comes beyond death, not in bypassing it. I have said it before, I know it cognitively, but this summer I experienced that truth and now know it even deeper—even as I’m still learning of the restoration God will provide on this side of my loss.

That really is the story of scripture, that God delivers us through suffering and loss not from it. Humanity’s ultimate deliverance, of course, comes from the ultimate suffering—the innocent suffering of Christ on the cross. The resurrection is, in fact, linear—death, and only then eternal life.

It’s a hard word in many ways. Who willingly embraces suffering? No one of their own strength and not for suffering’s sake alone. Instead, redemptive suffering requires our hearts to be set right—and it can serve to set our hearts right if we allow God to do a new work in us through it.

Thomas Merton in No Man Is an Island puts it this way:

If we love God and love others in him, we will be glad to let suffering destroy anything in us that God is pleased to let it destroy, because we know that all it destroys is unimportant. We will prefer to let the accidental trash of life be consumed by suffering in order that his glory may come out clean in everything we do.

If we love God, suffering does not matter. Christ in us, his love, his Passion in us: that is what we care about. Pain does not cease to be pain, but we can be glad of it because it enables Christ to suffer in us and give glory to his Father by being greater, in our hearts, than suffering would ever be.

So this summer was excruciating. I’m coming out of it—stronger, more experienced, better prepared for what God has ahead. But most of all, I’m even more confident that the eternal glory to come, of which I’ve seen only glimpses so far, truly will far outweigh these light and momentary afflictions (2 Corinthians 4:17).

Marybeth Baggett is professor of English at Houston Baptist University and serves as associate editor for MoralApologetics.com. She earned her PhD in Literature and Criticism from Indiana University of Pennsylvania, and — along with her husband— recently has published The Morals of the Story: Good News about a Good God (IVP Academic, 2018).

Editor’s note: R. Scott Smith has graciously allowed us to republish his series, “Making Sense of Morality.” You can find the original post here.

Between the time of the ancient Greeks and the Scientific Revolution, western ethics was dominated by religious traditions. I will give a broad overview of several key thinkers from Jewish and Christian thought. Could these ethical views preserve these core morals?

First I will focus on the Hebrew Scriptures. There, ethics are grounded ultimately in God’s moral character and thus what He commands. Those commands, or laws, were not arbitrary. Instead, He always would will what fits with His morally perfect character. Thus, it was a deontological (duty-based) ethical approach.

As God’s people, Israelites were to be like God. For instance, because God is just, holy morally pure and undefiled by sin (evil), and compassionate and loving, they too were to practice justice (Micah 6:8), be holy (Lev 19:2), and be compassionate and loving.

In addition, there was room for other forms of ethical reasoning. The wisdom literature appealed at times to utility (consequences) of actions (e.g., Prov 6:20-29). There also was room for self-interest (e.g., Deut 28:1-7, 15, where Moses spells out blessings of obedience, and the consequences of disobedience). There also was room for appeals to reason, or natural law. People should know particular moral principles based on how God has created them and nature (e.g., from observing nature, be diligent, Prov 6:6-11; do not slaughter pregnant women to extend one’s territory, Amos 1:13).

Also, Maimonides (d. 1204) lived in Spain, home of the Jewish intellectual center during the Islamic empire. He tried to synthesize Aristotle’s thought (which he received through Islamic sources) with the Mosaic Law, or Torah. To him, God’s revelation is perfectly compatible with natural law. Moreover, both sources give us knowledge of objective moral truths, which ultimately are grounded in God. As with Aristotle, Jewish thought has room for virtues, but the primary emphasis is obedience.

Christians draw ethics from both the Old and New Testaments. However, unlike Israel in the Old Testament, Christians do not live under a theocracy. Moreover, they are not under the Mosaic Law, but grace, to be in relationship with God. Still, they should obey the moral law out of love for God.

Specifically, they are to love God with all their being, their neighbors as themselves (Matt 22:37, 39), and one another as Jesus has loved them (John 13:34). They also are to care for the vulnerable (James 1:27, Luke 14:16-24) and, generally, to embody Jesus’ kingdom’s values. Moreover, there is a continued stress upon obedience, but with special emphasis upon heart attitudes (Matt 5:17-20). However, Christians cannot do this apart from the power of God’s Spirit in them. Virtues continue to matter, for Christians are to become like Christ, their telos (Eph 4:13, Col 1:28).

Augustine (d. 430) built upon the biblical teaching that God is intrinsically good and sovereign. Since God only does what is good, His creation is good, so He did not create evil. Instead, evil arose from humans’ feely willed rebellion against God. Evil, then, is spoiled, perverted goodness.

Augustine posited two cities, or kingdoms: that of humans, and that of God. Members of the city of man live after their sinful desires. At best, they can achieve a rough peace and justice, and they follow their love of themselves. In contrast, members of the city of God follow God’s Spirit, and they have the peace of God and with God. They are motivated by God’s love.

Augustine adopted the cardinal virtues and tied them to the theological ones, faith, hope, and love. Yet, he refocused the cardinal ones in terms of the love of God. Due humans’ sin, it is impossible to be truly virtuous by their own efforts.

As a Catholic, Aquinas (d. 1274) synthesized Augustinian theology with Aristotelian philosophy. Aquinas posited two realms that can be depicted variously: the heavenly and the earthly; revelation and reason; sacred and secular; supernatural and natural; and grace and nature. The supernatural realm includes the theological virtues, while the natural realm includes the cardinal, or natural, virtues.

In each pair, each realm is for the other. For instance, God cares for and gives revelation to creation, and creation is to glorify God. Also, revelation is intelligible by reason, though reason cannot exhaust what we know by revelation.

Aquinas also blends both deontological and virtue ethics. Christians should embody the theological and natural virtues, while non-Christians should embody the natural ones. So, his ethics applies universally, and we can know ethics by reason and revelation.

In all these Christian and Jewish views, there is a body-soul dualism, with the soul as humans’ essence. So, the virtues and commands are appropriate for humans due to their nature, and morals exist objectively. In these ways, it seems they can preserve our four core morals.

Thomas Aquinas, Summa Theologica, First Part of the Second Part (on law), and the Second Part of the Second Part (on virtues)

Augustine, City of God, and The Enchiridion

Robert M. Seltzer, Jewish People, Jewish Thought, 393-408

R. Scott Smith, In Search of Moral Knowledge, chs. 1, 3

R. Scott Smith is a Christian philosopher and apologist, with special interests in ethics, knowledge, and seeing the body of Christ live in the fullness of the Spirit and truth.

Sometimes in life tragic news shatters our plans, alters the direction of our lives, leaves us with a string of unanswered questions, and causes us to lose hope for a period of time. News such as this oftentimes comes in the form of a text message, phone call, letter, social media post, medical prognosis—or in my own case, when my wife and I recently heard these seven words in an ultrasound room:

“I’m so sorry. There is no heartbeat.”

You see, my wife and I found out around the time of my birthday in late August that we were expecting our fourth child, only to realize a few weeks later in an ultrasound room that we were actually expecting our fourth and fifth children. We were going to be the parents of twins! I remember feeling a profound sense of excitement (and if I am honest, I also felt a bit overwhelmed).

About a month after our first ultrasound appointment, preparing to enter the ultrasound room for the second time, we were thrilled to see our twins and also hear their little hearts beat. The appointment began with a quick scan of the first baby, allowing us the opportunity to see how much our first baby had grown. We were also able to hear our first baby’s heartbeat. Everything appeared fine until the ultrasound technician shifted her attention to the second baby, where we soon realized that something was wrong. After a few moments of attempting to detect a heartbeat, the ultrasound technician broke the news to us that our second baby did not have a heartbeat. Following a few moments of unbelief (and perhaps even denial), my wife and I locked eyes as tears began rolling down each of our faces. We were devastated.

In the days since receiving this news, we have cried together, prayed together, and reflected upon God’s truths together. Although there are many truths that I could share in light of losing one of our twins, four thoughts have consumed my mind.

First, God empathizes with us in our pain. Hebrews 4:15 says, “For we do not have a high priest who is unable to empathize with our weaknesses…” Jesus Christ, our high priest, not only shows compassion to those of us who are hurting, he takes to himself a joint feeling of our weaknesses—because he himself endured suffering, loss, mockery, abandonment, and temptation. Jesus experienced not only physical suffering, but also spiritual, emotional, and relational hardship, among other things.

Have you been rejected by friends before? So has Jesus. Have you been made fun of before? So has Jesus. Have you been ridiculed for your beliefs? So has Jesus. Have you lost someone you loved? So has Jesus. Have you experienced physical, emotional, or relational pain? So has Jesus. And here is the one that has been most comforting for us recently: Have you lost a child? So has God the Father. Although there are many other ways in which God can empathize with us in our specific instances of pain and suffering, here is the bottom line: God knows what it is like to be in our shoes; he took on human flesh, becoming one of us and walking in our shoes, experiencing many of the difficulties that we face today. This enables him to empathize with us, proclaiming, “I understand what you are going through. It’s tough. I’ve been there before.”

Second, we can trust God in our “why” moments. There are times in life when we wonder why something (usually something bad) has happened. In our “why” moments, and in all other moments, we can trust God because of who he is. The character of God is the foundation of our faith in him. Of course, the same is true with a close friend or a spouse—we trust the character of these individuals when we do not know why they are asking us to do certain things, and again, it’s because of who they are. However, unlike our human acquaintances, God is entirely holy (Is. 6:3), good (Ps. 136:1), loving (1 Jn. 4:8), just (Is. 61:8), sovereign (Acts 4:24), omnipresent (Ps. 139:7), omnipotent (Jer. 32:27), gracious (Ex. 34:6-7), merciful (Ex. 34:6-7), unchanging (Mal. 3:6), personal (Gen. 3:8), and so on.

God is also omniscient, which means that he knows all things, including the answers to all of our “whys.” Although we may not know “why” something has happened, such as the loss of a child, we can still trust God who knows why. As we understand who God is on a deeper level, we come to realize that because of his character, we are able to trust him in those things that we do not know or understand. Why? Because of who he is; he is trustworthy.

Third, God gives us what we need most: himself. Having gone through several tragedies in my lifetime, I am not convinced that we would be entirely satisfied even if God revealed to us his reasons for allowing something to happen. With our “answer” in hand, we would still be missing what we need most: God himself.

The day that my wife and I received the news about our twin’s passing, I read Job 38-42 and reflected on these words from C. S. Lewis, found in Lewis’s Till We Have Faces: “I know now, Lord, why you utter no answer. You are yourself the answer. Before your face questions die away. What other answer would suffice?”[1] This Lewis quote is very similar to what Job realizes about God in the last five chapters of the book of Job. Job does not get an answer; rather, he realizes that God is the Answer. What we need most in the face of tragedy is not an answer to a question; we need God, who is himself the Answer. God is not only what we need most, he is also what, or more correctly who, is best for us. Simply put, a mere answer in the form of a statement will not truly satisfy; we need something far greater: the Answer himself.

Fourth, God gives us others to help us through our pain. Oddly enough, in the week following the difficult news about our twin, I came across several newspaper clippings pertaining to my father’s sudden death in 1994. Despite reading each article carefully, one of the articles deeply moved me. The article, focusing on how the community where we lived in North Carolina at the time rallied around us, begins this way: “Sometimes the pain from a sudden tragedy can be made less hurtful by the love and acts of kindness which result.”

As human beings, we were never meant to go through life alone. God has given us others to help us through our pain, to meet the needs that we have, pray for us, encourage us, and so on. The pain that we experience as a result of something difficult in our lives is oftentimes either lessened or at least becomes more bearable when we allow others to minister to us amidst our pain. In the days since October 22, numerous family members, friends, coworkers, and students have come alongside us in order to weep with us, pray with us, encourage us, and bless us in so many other ways (meals, cards, etc.).

There is certainly a lot more that I could say, and I pray that God gives me opportunities to say more in the future—particularly to those who find themselves experiencing loss as we have experienced loss. For now, it is enough to remember that (1) God empathizes with us in our pain, (2) that we can trust God in our “why” moments, (3) that God gives us himself, and (4) that God provides others to help us through our pain. These four truths continue to assist us as we navigate the difficult season through which we are walking, and I am confident that these four truths will get us through whatever else may come our way in the future.

*Elyse Faith, our sweet girl who we never actually “met,” we love you and we cannot wait until the day we see you in heaven. Until then, we’ll cling to what your name means: faith in the promises of God.

Stephen S. Jordan currently serves as a high school Bible teacher at Liberty Christian Academy, a Bible teacher and curriculum developer/editor at Liberty University Online Academy, and he oversees the curriculum development arm of The Center for Moral Apologetics at Houston Baptist University. He possesses four graduate degrees and is presently a PhD candidate at the Liberty University Rawlings School of Divinity, where he is writing his dissertation on the moral argument. He and his wife, along with their three children, reside in Goode, Virginia.

[1] C. S. Lewis, Till We Have Faces (San Francisco, CA: HarperOne, 2017), 351.

Editor’s note: R. Scott Smith has graciously allowed us to republish his series, “Making Sense of Morality.” You can find the original post here.

Today, in the west, we live in a time with many different moral “voices” and competing claims. When I was a graduate student in Religion and Social Ethics at the University of Southern California from 1995-2000, this was quickly apparent. Many of my fellow grad students rejected any kind of objectively real morals. Instead, they saw morals as their own construct, which were based on a wide range of preferred views. One person, a Reformed Jew, tried to integrate her religious tradition with the insights of Jacques Derrida’s deconstructionism and the sociology of knowledge. Many rejected their Catholic roots and instead embraced some form of critical theory, which is deeply liberationist in spirit. Some followed Foucault and queer theory, while others embraced Nietzsche. Still others followed various feminist theorists.

Like them, many people think morality is simply “up to us”; morals are just particular to individuals or communities. Indeed, they are deeply suspicious of any claims that there are morals that transcend and exist independently of us. They think that to impose others’ morals, including “objective” ones, on people is deeply imperialistic and oppressive. After all, who are you to say what is right or wrong?

There also are different social visions that align with these moral viewpoints. For example, progressives seem to be secular, such that morals for society should be based on secular, public reasons, not narrow, sectarian, or religious reasons. Otherwise, how could we come together and be a society in which there are so many different, private moral visions?

Now, for those influenced by western thought, and especially those who have grown up in the west, it easily can seem that not only is this moral diversity the way things are, but also the way things should be. After all, in the west (and especially the U. S.), we prize the value of autonomy, which we understand as being free to determine our own lives. Coupled with the view that morals are basically “up to us,” we should expect there to be an irreducible plurality of viewpoints, norms, and values.

Over time, in the west a large number of competing moral theories have been advanced. But these did not come out of a vacuum. They have a history with many shaping influences, leading even to the mindset that morals are up to us. One of the things I will do in this series is to explore those shaping factors. Two of them are the Scientific Revolution, and the “fact-value split” in the late 1700s.

Despite this great plurality of ethical views, it still seems there are at least some core morals all people simply know to be valid. For instance, people want justice to be done. They may disagree about what constitutes justice, or their theories about justice. But, it seems people know that justice is good and should be done. Love is another virtue people know to be good. They may disagree about what the loving action should be, but they still seem to agree that we should be loving.

Image by Mary Pahlke from Pixabay

Besides these virtues, there are some principles that people simply seem to know are right. For instance, it seems people simply know murder is wrong. While some may disagree about what act should count as murder, nevertheless, we know that murder (as the intentional taking of an innocent person’s life) is wrong. I would add that rape is wrong too. These four morals seem to be core –we simply seem to know they are valid.

Some might add other moral principles and values to that short list. For example, for many, it is clear that genocide and chattel slavery are wrong. In this series, I will focus on those four core morals. I will look at the various types of ethical views in western historical context, to see if they can preserve those core morals. If a theory cannot do that, then it seems we should reject it. In that process, a key question I will ask is this: what kind of thing are these core morals? But, before I start that survey, I will explore the influences from the Scientific Revolution on our ethical thinking.

R. Scott Smith is a Christian philosopher and apologist, with special interests in ethics, knowledge, and seeing the body of Christ live in the fullness of the Spirit and truth.

In an episode of The Simpsons, the perpetually pious Ned Flanders is the representative of a theistic ethicist. Gerald J. Erion and Joseph Zeccardi explain:

In Springfield, Ned Flanders exemplifies one way (if not the only way) of understanding the influence of religion upon ethics. Ned seems to be what philosophers call a divine command theorist, since he thinks that morality is a simple function of God’s divine command; to him, “morally right” means simply “commanded by God” and “morally wrong” means simply “forbidden by God.” Consequently, Ned consults with Reverend Lovejoy or prays directly to God himself to resolve the moral dilemmas he faces. For instance, he asks the Reverend’s permission to play “capture the flag” with Rod and Todd on the Sabbath in “King of the Hill”; Lovejoy responds, “Oh, just play the damn game, Ned.” Ned also makes a special telephone train room in Reverend Lovejoy’s basement as he [Ned] tries to decide whether to baptize his new foster children. Bart, Lisa, and Maggie, in “Home Sweet Home Diddily-Dum-Doodily.” (This call prompts Lovejoy to ask, “Ned, have you thought about one of the other major religions? They’re all pretty much the same.”) And when a hurricane destroys his family’s home but leaves the rest of Springfield unscathed in “Hurricane Neddy,” Ned tries to procure an explanation from God by confessing, “I’ve done everything the Bible says; even the stuff that contradicts the other stuff!” Thus, Ned apparently believes he can find solutions to his moral problems not by thinking for himself, but by consulting the appropriate divine command. His faith is as blind as it is complete, and he floats through his life on a moral cruise-control, with his ethical dilemmas effectively resolved.

I thought of this passage the other day as I was working my way through Jane Sherron De Hart’s compelling biography of Ruth Bader Ginsburg. Although Ginsburg had pride in her Jewish heritage, it was eventually more for its social dimensions than religious ones. De Hart writes about one of the exceptions:

There was also one other factor that might have indirectly contributed to [Ginsburg’s] success, though it did not occur to Ginsburg at the time—the age-old connection between Judaism and the law. The Torah (the five books of Moses) functioned as the original constitution for Jews. In the centuries following their exile from the land of Judea, rabbis and scholars in scattered Jewish communities had to figure out how to apply the Torah and its multiple commandments to seemingly insoluble problems of law and ritual. How could a common standard of behavior be maintained in the face of new sociopolitical, economic, and technological developments?

The result was the Talmud—a body of debates and opinions emphasizing legal argumentation based on the precedent of Mosaic law. Issues were examined from every possible angle, though room was always left for further interpretation in the face of ever-changing circumstances. The pattern of thought and methodology used to create the Talmud two millennia ago is remarkably similar to the kind of thinking demanded in law schools today. Ginsburg herself later elaborated on this theme in the introduction to a book about her Jewish predecessors on the Supreme Court. “For centuries,” she explained, “Jewish rabbis and scholars have studied, restudied, and ceaselessly interpreted the Talmud, the body of Jewish law and tradition developed from the scriptures. These studies have produced a vast corpus of Jewish juridical writing that has been prized in that tradition.”

Making Ned Flanders one’s foil instead of, say, a Jewish sage steeped in the Talmud renders quite a bit easier the task of depicting religious folks as doltish numbskulls uninterested in thinking hard. It is also a quintessential example of constructing a straw man. In truth, whether in the interpretation of the Old Testament or New, good exegesis is hard work. It is done according to solid, principled logarithms of hermeneutics, taking into account the often multifarious aspects of context. The Bible itself tells us to study to show ourselves approved, rightly dividing the word of truth (2 Tim 2:15), which presumably suggests we can wrongly divide the word of truth. When, as is often the case, what scripture teaches are general principles, there is a great deal of labor called for in applying them to specific and concrete situations. It is hard work, taking real thought, not floating through life on cruise control. That believers on occasion—intelligent and informed ones at that—don’t always see eye to eye on how best to exegete a passage and understand its import is evidence that the interpretive task is no easy matter, and often far from a no-brainer. For one who takes, say, scriptural commands seriously, rightly understanding them includes all the following: application of general principles to specific situations, each with its own unique features, extenuating circumstances, and mitigating factors; contending with invariable and vexed hermeneutical complexities; disambiguating between the timeless and transcultural, on the one hand, and the contingent and culturally conditioned, on the other; studying societal, biblical, and historical contexts in rich detail; engaging both heart and mind and communities in conversation; something at least resembling reflective equilibrium; precedent, synthesis, extrapolation, and more besides.

Ned is a funny character, no doubt, but hardly the paradigm of a thoughtful theist.

David Baggett is professor of philosophy and Director of the Center for Moral Apologetics at Houston Baptist University.

A key decision I had to make early in my year as acting dean was whether to be a candidate for a regular 3-year term as dean. After discussing the matter with friends and praying about it (though I suspect not sufficiently), I decided that the College would be best served by my not being a candidate, thereby lending more credibility to my being an honest and impartial broker between competing departmental objectives. I wanted the year to achieve the healing of animosities and distrust of administration within the College. My motives were good, I think, but I’m not sure my judgment was sound, especially in view of the person who was selected for the job after a nationwide search.

Joachim (“Kim”) Bruhn was a portly, friendly man who generally made a good first impression. However, within a few months his jolly “Hello, I’m Kim Bruhn, and I’m new here” began to wear thin, and his handling of the job proved less than satisfactory. One staff member observed that his personality and character were “a mile wide and an inch deep.” He had grand ideas about where the College should go and how it should get there, but he was terrible when it came to details. And on top of that, he had very flexible standards of telling the truth. He relied heavily on his staff to handle details, and so he was not always immediately and responsibly aware of exactly where the College’s finances stood nor what was the state of day-to-day operations. All of this meant that often I found myself being asked to explain or defend policies and decisions that I either lacked information on (because he had failed to tell me) or felt were on shaky ground.

I oversaw the College’s dealings with campus service units, such as Admissions and Registration and Records, and in doing so I was able to trade on relationships I had built during my year as Acting Dean. They trusted me, but they were sometimes puzzled by the difference in what they heard from Dean Bruhn and what they heard from me. Faculty in general did not hold Kim in high regard, and my close association with him tarnished my character with them sometimes. All these frustrations led to my deciding to resign as Associate Dean after serving two years.

When I informed Provost Eugene Arden, my friend and mentor over the years, he asked me out to lunch and made a strong pitch for me to stay on for another year. He argued that I was among the top 10% of people he had observed over the years in my aptitude for administration and that if I toughed it out I would have a good potential for an administrative career. I think perhaps he was already seeing that Kim Bruhn would not be approved for a second term as Dean, and that I was in a good position to succeed him. On the other hand, if I resigned (whatever my reasons), it would be a blot on my record and a hindrance to my being chosen for future administrative jobs. However, I was not willing to endure another year of working with Kim Bruhn and felt morally obligated to resign in order to disassociate myself from his dishonesty. In retrospect, that may have been an exercise of poor judgment. I think I was more concerned with my reputation than with whether the Lord wanted me persevere or give up.

In December of 1975, a disrupting event happened in Module 8 that turned out to have personal consequences for me. Early one morning, I received a call that a fire had broken out in our set of modules. (The sage comment of the Fire Warden when he assessed it was, “It appears to have been either an accident or arson.”) When I arrived on campus, I found that there had been considerable damage in Module 8, especially in a room where most of my campus library was stored. Later in the day, Laquita and I were dismayed at how many books were scorched and water-logged. We had to leave things in place until the insurance people had reviewed the scene in order to process the school’s claim for damage compensation. A good proportion of my books had to be written off for any remaining market value. We finally received our part of the school insurance settlement and were ready to move the books home to do whatever repairs we could. The year before this, we had bought a house in an attractive neighborhood about ten minutes away from the campus. We didn’t quite have the required down payment (1/3 of the cost in those days), so we swung a short-term bank loan for the balance and closed the deal. In August of 1974, we moved into 9 Adams lane in Dearborn, where we lived for the next 44 years. It was here that we moved the damaged books, storing them in the basement while we salvaged what we could, which turned out to be a majority of them.

Then, someone suggested we look into our homeowners’ insurance policy to see if there might be some recompense from them for the damaged books. We filed a claim, and wonder of wonders, we received a check for almost exactly the amount of our short-term loan! That incident has been a standard story in our history of incidents illustrating the Lord’s special provision in times of need. In addition, the great increase in my base salary during my years in administration had incremental effects in subsequent years, and the final result was a very healthy retirement package that even now is supplying the bulk of our retirement income. God’s supply of our financial resources over the years has kept us from being in debt except for one short term mortgage. That is one tangible result of my year as Acting Dean.

Dr. Elton Higgs was a faculty member in the English department of the University of Michigan-Dearborn from 1965-2001. Having retired from UM-D as Prof. of English in 2001, he now lives with his wife in Jackson, MI. He has published scholarly articles on Chaucer, Langland, the Pearl Poet, Shakespeare, and Milton. Recently, Dr. Higgs has self-published a collection of his poetry called Probing Eyes: Poems of a Lifetime, 1959-2019, as well as a book inspired by The Screwtape Letters, called The Ichabod Letters, available as an e-book from Moral Apologetics. (Ed.: Dr. Higgs was the most important mentor during undergrad for the creator of this website, and his influence was inestimable.

My family arrives at Grandma’s house. She exclaims as we pile out of the car, “The only thing about saying ‘hello’ is I’ve gotta say ‘goodbye’”. Saying “hello” implies saying “goodbye”; arriving suggests leaving; Jesus’ coming means Jesus’ going. Why does Jesus leave? Why must life have such parting and departing, particularly at life’s end?

Jesus’ disciples wonder the same thing. Thursday evening before he is crucified, Jesus says to his disciples, “Little children, I am with you only a little longer”. “Lord, You just got here…you’ve been saying the last three years, ‘Follow me’.” Now you’re saying the opposite, “Where I am going, you cannot follow me now…A little while, and you will no longer see me” Jesus’ disciples are in shock. Jesus, the One whose Kingdom is to have no end and who “will reign over the house of Jacob forever”, is departing?

This is the background for Jesus’ heartwarming word to his disciples, “Let not your heart be troubled. Believe in God and believe also in me. In my Father’s house there are many dwelling places. If it were not so, would I have told you that I go to prepare a place for you?”

“Let not your heart be troubled” . The word “troubled” is full of trouble: it pictures a horse confronting a coiled rattlesnake, or a hurricane agitating the sea. Being left alone by the Savior to a world of darkness and terror troubles the heart. What’s troubling you? Today, I do not know anyone who is not troubled; indeed, Jesus himself was ‘troubled’. At the ‘Last Supper’ as he foresees his betrayal, he ‘was troubled in spirit’. The shade of meaning Jesus uses in the tense of his word, “do not be troubled”, looks beyond the troubling moment. It is a commanding imperative coming out of eternity: “Do not go on letting your heart be troubled”; “do not persist in being troubled.” Though the immediate impact of a coiled rattlesnake in your path makes your heart pound, do not continue to be agitated. Why not? That brings us to Jesus’ second imperative. The first imperative only works because of this second imperative. It is the antidote for your troubled heart: “Believe in God and believe also in me.” If you trust in God, you will trust in Jesus Christ. If you trust in Jesus Christ, then you trust in God. Once this trust is established, then your future is established: you are not only going to see Jesus again; you are going to be with Him again - forever!

“In my Father’s house there are many dwelling places. If it were not so, would I have told you that I go to prepare a place for you? And if I go and prepare a place for you, I will come again and will take you to myself, so that where I am, there you may be also.” Look at the phrase, “In My Father’s House”. In England, one refers to the British Royal Family as the ‘House of Windsor’. Similarly, ‘my Father’s House’ refers not to a structure , but to the Father’s Family or his Kingdom. ‘Father’s House’ is the Father’s realm where the Father resides.

Keeping that in mind, consider further. “In my Father’s house, there are many _____.” There is no exact translation of the word left blank variously translated, ‘mansions’, ‘rooms’, or ‘dwelling places’; a better term is ‘traveler’s rest’. The idea of ‘traveler’s rest’ seems to be a place where weary pilgrims on a long and trying journey find long-term sanctuary. A ‘traveler’s rest’ is a haven removed from suffering, from the weary struggles of conflicts and battles, and the dangers of dark forces.

In JRR Tolkien’s Lord of the Rings , the Hobbit Frodo Baggins is on a perilous and strenuous odyssey to save the world from the Dark Forces. At a moment of impending death and capture, he is removed to safety to Rivendell. Rivendell is a “traveler’s rest’ in a strategically fortified gorge offering him security and peaceful protection. Here he convalesces in perfect safety.

Last October, my wife Pam and I had an ambitious day of travel. We toured American Founder John Adams’ home and then drove across Boston. Heading up into New Hampshire, we ambled around Robert Frost’s farm. At early dusk, we arrived at our final destination, the New Hampshire country inn, Manor on Golden Pond . In desperate need of country refuge and refreshment, we found a ‘traveler’s rest’! We still savor the gourmet dinner in the elegant, paneled dining room; we see the view of Golden Pond out the picture window of our bedroom.

“In my Father’s house there are many permanent, traveler’s rests.” Is there one for you? Jesus says to his disciples, ‘I am departing to ready it for you.’ The Lord of Hosts is making up His disciple’s residence. “If it were not so, I would have told you.’ This is a strong statement. Jesus’ word is at stake. One more thing: ‘If I go and prepare a place for you, I am coming again and I will take you with me to my home. So that where I am, there you may be also.’

Historically, English Lords, such as Lord Grantham in Downtown Abbey, invite people to their estates like ‘Downtown Abbey’ for ‘do’s’ - like his hunting party. People come for days to the country and live off the hospitality of the Lord of the manor.

The Lord of the heavenly realm has departed to go ahead of his disciples; He’s preparing eternal residences - ‘traveler’s rests’ - even one for you! He very much wants you to join him there. So that where He is, ‘there you may be also’. Don’t you want to be with Him and his friends? Knowing this means, you only have one final parting, and then no more ever again. In the meantime, ‘do not go on letting your heart be troubled...trust in God and trust in Jesus Christ!

Tom is currently a retired Elder in the Virginia Annual Conference. He has pastored churches in Virginia, California and England. Studying John Wesley’s theology, he received his Ph.D. and M.A. degrees from the University of Bristol, Bristol, England and his Master of Divinity degree from Asbury Theological Seminary. While a student, he and his wife Pam lived in John Wesley’s Chapel “The New Room”, Bristol, England, the first established Methodist preaching house. Tom was a faculty member of Asbury Theological Seminary. He has contributed articles to Methodist History and the Wesleyan Theological Journal. He and his wife have two children, daughter Karissa, who is an attorney in Richmond, Virginia, and, John, who is a recent graduate of Regent University. Being a part of the development of their grandson Beau is a rich reward. Tom enjoys a good book by a crackling fire with an English cup of tea. His life text is, ‘Jesus, confirm my heart’s desire, to work and speak and think for thee’.

In previous installments I have spoken of three experiences from my past—from my childhood, in fact—that shaped me as a moral apologist. These were the following: being raised in the holiness and camp meeting tradition, watching Mister Rogers’ Neighborhood, and seeing a poignant television commercial about a relief organization’s work in an underprivileged part of the world. All of those experiences were what we might call positive ones—inspiring me to think about what moral goodness is, what it looks like, and what it feels like.

Not all of the experiences that shaped me, though, were positive. Like all of us, there were also plenty of negative experiences from my past, so today I’m going to share one of those in particular. It is an especially difficult chapter from my past to share. It is the source of a fair amount of shame, because it was no small moral infraction.

More than once I had the opportunity to put a stop to a particular kid getting bullied. He was an easy target, not a physically strong boy, and in various ways an outlier, just not fitting in. Although more than once I had a strong impulse to reach out, to protect him, to include him, to befriend him, I did not. And on more than one occasion I actually saw him getting cruelly bullied and did nothing about it. I have thought about this many times since then, and I am still ashamed for not doing the right thing.

In fact, my resounding silence and abject failure to do the right thing was actually doing the radically wrong thing. My failure to act was wicked, and the reason, I’m convinced, I felt guilty about it is because in fact I was guilty. The feeling was indicative of a deeper problem, tracking the reality of an objective condition. I knew to do right and failed to do it, and in so failing I did something unspeakably awful. I know that now, but I knew it then, too.

In his Confessions, Augustine shared with laudable transparency his own painful childhood lesson in depravity. The example seems trivial—stealing pears—but the key to grasping its import is understanding that beneath its garden-variety nature lurked something far more sinister. He elaborated like this:

I wanted to carry out an act of theft and did so, driven by no kind of need other than my inner lack of any sense of, or feeling for, justice. Wickedness filled me. I stole something which I had in plenty and of much better quality. My desire was to enjoy not what I sought by stealing but merely the excitement of thieving and the doing of what was wrong. There was a pear tree near our vineyard laden with fruit, though attractive in neither [color] nor taste. To shake the fruit off the tree and carry off the pears, I and a gang of naughty adolescents set off late at night after (in our usual pestilential way) we had continued our game in the streets. We carried off a huge load of pears. But they were not for our feasts but merely to throw to the pigs. Even if we ate a few, nevertheless our pleasure lay in doing what was not allowed.

Such was my heart, O God, such was my heart. You had pity on it when it was at the bottom of the abyss. Now let my heart tell you what it was seeking there in that I became evil for no reason. I had no motive for my wickedness except wickedness itself. It was foul, and I loved it. I loved the self-destruction, I loved my fall, not the object for which I had fallen but my fall itself. My depraved soul leaped down from your firmament to ruin. I was seeking not to gain anything by shameful means, but shame for its own sake.[1]

Of course all human beings have their redeeming characteristics and moral strengths—each of us is made in God’s image, after all. We are far from being as bad as we can be. Still, only after recognizing our need to be forgiven—our having fallen short of the moral law, both our draw and repulsion to the good, our love and hate of shame, our indulgence of darkness, our taste for wickedness—are we able to apprehend just how good is the good news of the gospel.

In an essay called “Christian Apologetics,” in God in the Dock, C. S. Lewis identifies salient features of those in his generation, and his analysis is perhaps even timelier today. Among such features was skepticism about ancient history and distrust of old texts; another one—most relevant for present purposes—was that a sense of sin is almost totally lacking. Lewis writes that

Our situation is thus very different from that of the Apostles. The Pagans … to whom they preached were haunted by a sense of guilt and to them the [g]ospel was, therefore, “good news.” We address people who have been trained to believe that whatever goes wrong in the world is someone else’s fault—the Capitalists, the Government’s, the Nazis’, the Generals’, etc. They approach God Himself as His judges. They want to know, not whether they can be acquitted for sin, but whether He can be acquitted for creating such a world.

In attacking this fatal insensibility it is useless to direct attention (a) To sins your audience do not commit, or (b) To things they do, but do not regard as sins. They are usually not drunkards. They are mostly fornicators, but then they do not feel fornication to be wrong. It is, therefore, useless to dwell on either of these subjects. (Now that contraceptives have removed the obviously uncharitable element in fornication I do not myself think we can expect people to recognize it as sin until they have accepted Christianity as a whole.)

I cannot offer you a water-tight technique for awakening the sense of sin. I can only say that, in my experience, if one begins from the sin that has been one’s own chief problem during the last week, one is very often surprised at the way this shaft goes home. But whatever method we use, our continual effort must be to get their mind away from public affairs and “crime” and bring them down to brass tacks—in the whole network of spite, greed, envy, unfairness, and conceit in the lives of “ordinary decent people” like themselves (and ourselves).[2]

In class I sometimes ask how best to address this ubiquitous notion nowadays that none, or at least hardly any, of us are deep sinners in need of forgiveness. It is a challenging situation to confront, but very often a prominent part of our current context. Perhaps one way is to talk about one’s own failures, rather than our neighbor’s. For another, Lewis directed folks to consider their chief sin of the previous week. Yet another approach might be to reframe the question like this: Ask folks to consider the biggest mistake they ever made, and then ask them what went into that mistake. Specifically, is there, in their resultant regret, any moral element? That may edge people closer to considering their moral failures.

Of course, for Christians encouraging such reflection, the point is not to put people under condemnation to leave them there, but to share the news of liberation from guilt and reconciliation with a loving God anxious to save them to the uttermost. Not the false liberation of defiantly denying, or simply failing to recognize, one’s guilt, but the true freedom that comes from knowing the truth.

I also hope one day I run into the man who had been that bullied boy, and tell him I am sincerely sorry for my wretched cowardice and complicity in cruelty.

David Baggett is professor of philosophy and Director of the Center for Moral Apologetics at Houston Baptist University.

Anyone who is anyone in apologetics has heard of the kalam cosmological argument. Short, concise, and powerful; the kalam argument notes the causal agency behind the origins of the universe. Simply put, the kalam argument holds:

1. Everything that begins to exist has a cause.

2. The universe began to exist.

3. Therefore, the universe has a cause (C&M, 102).

After further researching the kalam argument, it was discovered that an ontological reality underlies the argument. That ontological reality is that one cannot escape the necessity of a Cosmic Mind for three reasons.