Models of Oral Tradition and the Ethics Behind Accurate Transmission

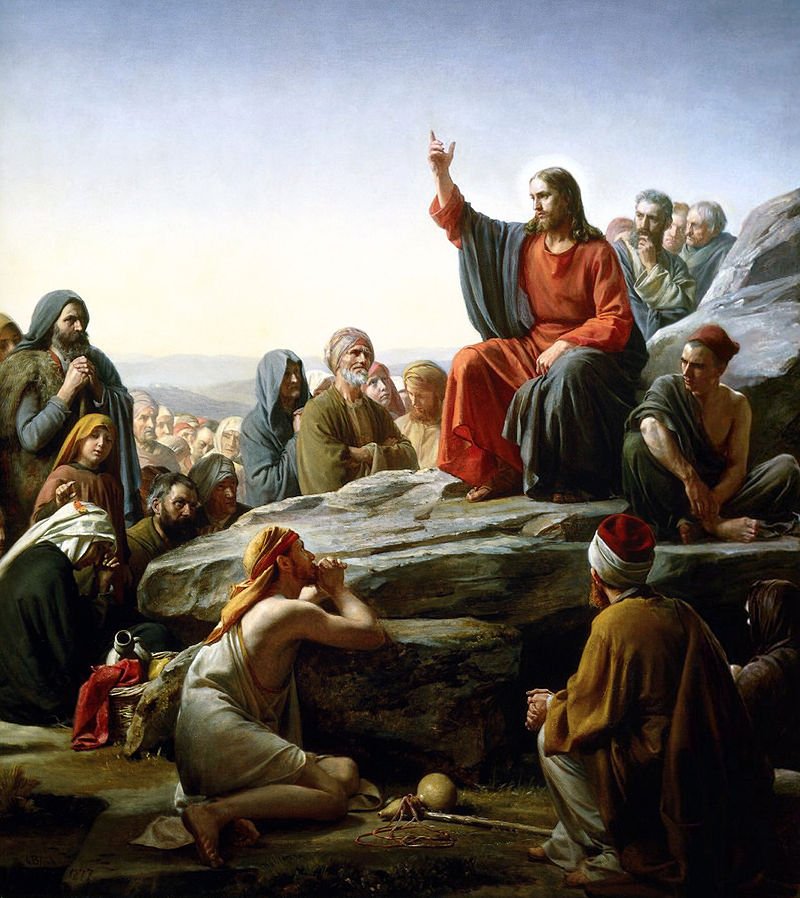

/The Sermon on the Mount, Carl Bloch

In a heartfelt testimony, Bart Ehrman describes the origins of his descent from a fundamentalist Christian to an atheist-leaning-agnostic in his book Misquoting Jesus. The central factor in Ehrman’s doubt was the differences found in the Gospel texts. The catalyst of his departure was an apparent error in Jesus’s quotation of 1 Samuel 21:1–6 along with apparent differences in the Gospels’ presentation of the life of Jesus.[1] Ehrman is not alone. While Ehrman is correct in that Christianity and Judaism are “bookish religions,”[2] James D. G. Dunn is also correct in noting that properly understanding the transmission of early Jesus requires a shift in one’s default thinking to an “oral mind-set.”[3] At the end of the day, it must be asked how much liberty early writers were given to report the deeds and teachings of Jesus. If the writers of the New Testament intentionally tried to mislead individuals, then there lies an ethical problem behind the formation of the New Testament Gospels. Let us look at the three models of oral traditions and which one most closely aligns with the New Testament texts.

Informal Uncontrolled Model—Bultmannian Viewpoint

The first model is advocated by German scholar Rudolf Bultmann and is called the informal uncontrolled model. In his book Jesus and the Word, Bultmann shows a striking similarity to Ehrman’s concepts as he writes, “I do indeed think that we can know almost nothing concerning the life and personality of Jesus, since the early Christian sources show no interest in either, are moreover fragmentary, and often legendary; and other sources about Jesus do not exist.”[4] Bultmann does not deny that a genuine Jesus tradition is found in the Gospels, but holds that they have faded from view. In this model, the transmission of the Jesus traditions was informal because of the lack of an official teacher to pass along (i.e., παραδιδωμι) the information, and it was uncontrolled since the community exercised great fluidity as the data was changed and shaped according to the needs of the time.[5]

Formal Controlled Model—Scandinavian School

In stark contrast with the informal uncontrolled model, Scandinavian scholars such as Birger Gerhardsson, Harald Riesenfeld, and Samuel Byrskog contend that the church had far more control over the Jesus traditions than the Bultmannian school conveyed. As Riesenfeld and the Scandinavian school deduced, the παραδιδωμι of the Jesus tradition was formal in the sense that it was entrusted to a special school of disciples, and it was controlled in the sense that the key features were memorized and preserved.[6] In his classic yet controversial book Memory and Manuscript, Gerhardsson compares the early transmission of the Jesus traditions to the παραδιδωμι (i.e., handing down) of the Oral Torah,[7] which was set forth with care using mnemonic devices, written notes, repetitions, and with a great concern for accuracy.[8] Thus, “Jesus is the object and subject of a tradition of authoritative and holy words which he himself created and entrusted to his disciples for its later transmission in the epoch between his death and the Parousia.”[9] But what about the portions of Scripture that seem to present variations in the material? Gerhardsson holds that the traditions were more comparable to haggadic material than halakhic material[10] which permits a wider margin of variation. Thus, one should anticipate some variations in the retelling of the material while also maintaining a high scrutiny for truth and accuracy.[11]

Informal Controlled Model—Kenneth Bailey

A third model is provided by Kenneth Bailey in an article written for Themelios Journal, which he calls the “informal controlled model.”[12] The informal controlled model is an ancient methodology are transmitted by a community called the haflat samar.[13] Certain individuals of the community memorize the material and recite it to the community. The elders of the community also memorize the material and offer correction if the reciter should err in his retelling of the story or teachings. While the storytellers were given some license to adapt the material, the core essential data must remain the same. Bailey estimates that no more than 15 percent of the story could be changed to permit interpretations and applications, but even then, the essential markers of the material could not be altered.[14] Thus, for Bailey, the material is informal in the sense that the community is involved with the preservation of the material and controlled due to the insistence of the community to accurately convey and παραδιδωμι truthful information that accurately conveys what one said and did.

Conclusion

From my continued research, the New Testament Gospels seem to convey a blend of the Scandinavian formal controlled model and Bailey’s informal controlled model. The early credal material assuredly matches Gerhardsson’s and the Scandinavian model. However, the parables seem to hold a greater similarity with Bailey’s informal controlled model allowing for greater flexibility. It may be that different portions of the New Testament Gospels swing from one side of the pendulum to the other. Regardless of whether a passage is found in Gerhardsson’s or Bailey’s model, both emphasize the early Christian community’s commitment to accuracy and truthfulness. Therefore, one can take confidence in the early church’s commitment to ethical integrity and truthful transmission. The early Christians believed that they were preserving the message of Jesus whom they believed was the Son of God. As such, models such as Bultmann’s do not consider the early ethical standards of the first church. Also, Bultmann’s model does not seem to cohere with the biblical data. Craig Blomberg puts it best by saying, “we may confidently declare that the approach to oral tradition (that is, the formal controlled and informal controlled models) is far more likely to approximate historical realities than those of Funk, the Jesus Seminar, and others who promote the model of informal, uncontrolled tradition.”[15]

About the Author

Brian G. Chilton is the founder of BellatorChristi.com, the host of The Bellator Christi Podcast, and the author of the Layman’s Manual on Christian Apologetics. Brian is a Ph.D. Candidate of the Theology and Apologetics program at Liberty University. He received his Master of Divinity in Theology from Liberty University (with high distinction); his Bachelor of Science in Religious Studies and Philosophy from Gardner-Webb University (with honors); and received certification in Christian Apologetics from Biola University. Brian is a member of the Evangelical Theological Society and the Evangelical Philosophical Society. Brian has served in pastoral ministry for nearly 20 years and currently serves as a clinical chaplain.

https://www.amazon.com/Laymans-Manual-Christian-Apologetics-Essentials/dp/1532697104

© 2022. MoralApologetics.com.

[1] Bart D. Ehrman, Misquoting Jesus: The Story Behind Who Changed the Bible and Why (New York, NY: HarperOne, 2009), 9.

[2] Ibid., 20.

[3] James D. G. Dunn, The Oral Gospel Tradition (Grand Rapids, MI; Cambridge, UK: Eerdmans, 2013), 49.

[4] Like Ehrman, Bultmann argues that the earliest community was not interested in preserving historical information about Jesus and his messages, but they were rather more interested in the situations facing the evolving church. Rudolf Bultmann, Jesus and the Word (New York, NY: Scribners, 1958), 8.

[5] Historical accuracy was not the primary focus in this model. While Ehrman and the Jesus Seminar popularized this model, this is far from the only one.

[6] Riesenfeld argued that the “words and deeds of Jesus are a holy word, comparable with that of the Old Testament, and a handing down of this precious material is entrusted to special persons.” Harald Riesenfeld, “The Gospel Tradition and Its Beginnings,” in The Gospel Tradition (Philadelphia, PA: Fortress, 1970), 19.

[7] Oral traditions associated with the Torah and the memorization of the written texts.

[8] Birger Gerhardsson, Memory and Manuscript: Oral Tradition and Written Transmission in Rabbinic Judaism and Early Christianity (Grand Rapids, MI: Eerdmans, 1998), 335.

[9] Riesenfeld, “Gospel Tradition and Its Beginnings,” Gospel Tradition, 29.

[10] Halakhic material (Heb. “the way”) contained the totality of the laws that were passed down since biblical times and largely from written sources. Haggadic material—haggadah meaning “tales”—contains non-legal material that was offered to preserve historical events, folklore, and moral teachings that were part of the Jewish Oral Law (תורה שבעל פה). The Haggadah has passed along important teachings and interpretations, while also allowing for a more spiritual and allegorical dimension.

[11] Gerhardsson, Memory and Manuscript, 335.

[12] Kenneth E. Bailey, “Informal Controlled Oral Tradition and the Synoptic Gospels,” Themelios 20, 2 (1995): 5.

[13] Samar is an Arabic cognate of the Hebrew shamar which means “to preserve.” Ibid., 6.

[14] Ibid., 7.

[15] Craig L. Blomberg, “Orality and the Parables: With Special Reference to James D. G. Dunn’s Jesus Remembered,” in Memories of Jesus: A Critical Appraisal of James D. G. Dunn’s Jesus Remembered, Robert B. Stewart and Gary R. Habermas, eds (Nashville, TN: B&H Academic, 2010), 125–126.