Why? Apologetics, Moral Apologetics, and You

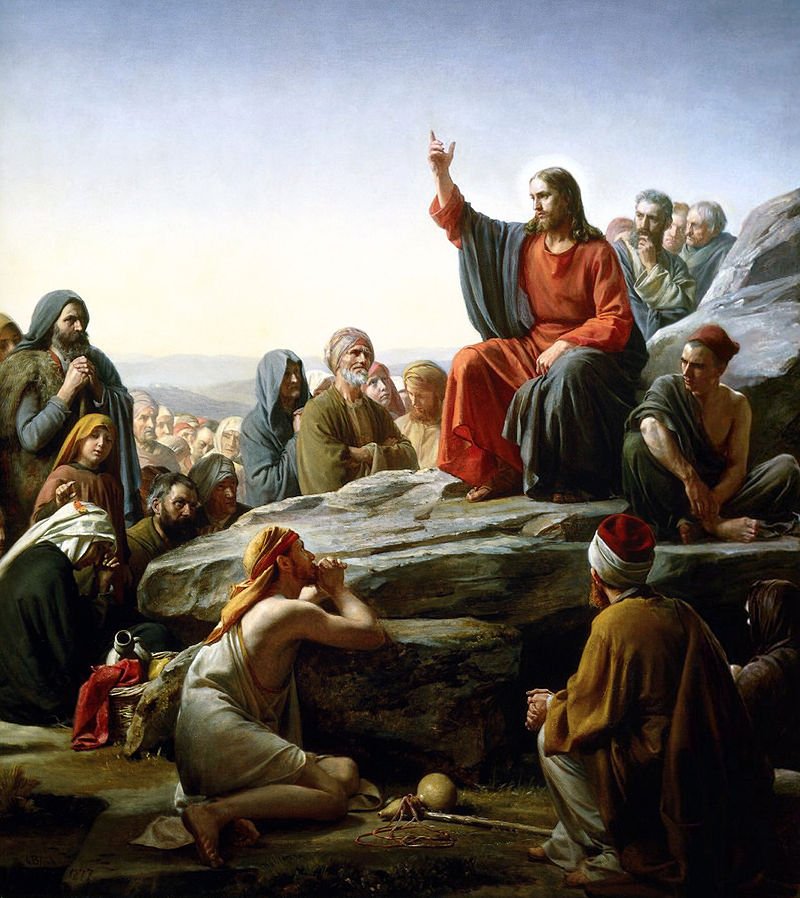

/Saint Paul delivering the Areopagus Sermon in Athens, by Raphael, 1515.

I recently heard of a key administrator in a Christian university who questioned the legitimacy of continuing to fund the study of apologetics because the leader found the concern to defend the faith irrelevant and distracting from more pressing matters of ministry. Let that sink in for a moment. Apologetics is irrelevant and distracting? Sadly, there are many who agree with this leader’s concerns, and many more who would probably not be so bold as to relegate apologetics to a matter of irrelevance and distraction but who, nonetheless, have little time, energy, or resources to devote to defending the faith once delivered. Rather than cursing the darkness I find in this lamentable reality, I want to light a candle and, hopefully, shed light on why apologetics matters. My earnest conviction is that, far from irrelevance and distraction, apologetics is of the essence of the church’s mission in our post-modern, post-Christian, post-everything culture. So, here are three questions for those who are unsure that apologetics matters today.

First, why apologetics? Stated rather bluntly, the answer to this question is one word: obedience. Apologetics is commanded in Scripture, and the command is not isolated to academicians or those with specialized rhetorical gifts. Quite the opposite is true. Apologetics is the calling, the directive, the command to every believer. 1 Peter 3:15 makes this unequivocally clear, stating that each believer must “sanctify the Lord God in your hearts, and always be ready to give a defense to everyone who asks you a reason for the hope that is in you.” Pretty straightforward, right? Indeed, it is, and as Peter wrote to everyday believers who found themselves suffering for their faith amid a hostile culture, he also wrote to us. Peter’s command is not labored to make his point, and that’s just the point—apologetics is the straightforward expectation of all who trust in Christ even when the world around them doesn’t. All of us are commanded, in the context of setting apart Christ as Lord of our lives, to always be ready to defend our faith, our hope, our reasonable trust in the promises of God found in His word and manifested in our lives. Doing so is a matter of obedience, and not doing so is a matter of disobedience. It’s that simple. So, rather than questioning the relevance and legitimacy of apologetics, the real question is whether we will obey God. Apologetics is about doing our duty. Of course, there are plenty of other reasons to make a defense of our faith, including the help apologetics affords in clearing obstacles to evangelism, the need to strengthen the faith of those who struggle, and the way in which apologetics enflames the soul with deeper love for God in the heart and mind. But when we reduce the matter to its bare minimum, doing apologetics is a matter of obeying God.

Second, why moral apologetics? Given that there are many ways to “do” apologetics, including answering questions about the reliability of the Bible, providing evidence concerning the resurrection, offering arguments for the existence of God based on the cosmos, and so on, the focused concern of MoralApologetics.com is to promote a particular type of apologetic engagement, namely, moral apologetics. The driving concern in moral apologetics is to begin with moral facts, moral knowledge, moral rationality, and moral transformation, reasoning thereby with the mind and heart to the existence of God. Not just any god, by the way, but a personal God who is the source of all morality, of all good, and who calls and graciously enables His creatures to find their truest self and greatest happiness in a life of righteousness and holiness reflective of His divine nature. While there are important nuances and careful qualifications that can and should be made by moral apologists, the fundamental reason moral apologetics matters is because all people are innately aware of a moral sense that permeates the very fabric of human existence. We know what right looks like, we know when justice has been violated, and we know that guilt is a pervasive human struggle. It is precisely at these points that the moral apologist can enter into the angst and struggle of human existence on common ground with every other person. Moral apologetics provides a touchpoint, a genuine connection between God’s goodness and humanity’s moral wantonness and frailty. In my experience as an apologist, many times I have started from a moral connection and found a ladder of sorts to climb from morality to questions of explicit religious concerns, and especially Christian ones. I hasten to add that moral apologetics is not the only starting point for a faith conversation, and sometimes it may not be the best starting point given the particulars in play in each dialogue with an unbeliever. What moral apologetics does provide, though, is an accessible and universal “sameness” from which I can talk with others about their struggles, the world, and the hope God offers in Jesus Christ. So, why moral apologetics? From my vantage point, it is usually the most direct route to move from the question to the questioner at a time when the vast majority of struggles humanity encounters are principally of a moral nature. Moral apologetics just makes sense as a beginning point in my efforts to obey God’s command to give a defense for the reason I find my highest and surest hope in Jesus Christ.

This brings me to the final question. Why not you? Given that apologetics is a matter of obedience to God’s good commands, and that moral apologetics provides a reasonable and plausible starting point for discussing matters of ultimate reality and the Gospel of Jesus Christ, why would you not commit to becoming a better apologist? Why not take your place among the ranks of God’s people who are His ambassadors of truth and goodness in a world beset with lies and wickedness? I can’t think of anything more legitimate and relevant.

Dr. Thomas J. Gentry (aka., TJ Gentry) serves as the pastor of First Christian Church of West Frankfort, Illinois, the Executive Editor of MoralApologetics.com, and Executive VP of Bellator Christi Ministries. Dr. Gentry is a world-class scholar holding 5 doctorate degrees and 6 masters degrees. Additionally, he is a prolific writer as he has published 7 books including Pulpit Apologist, Absent from the Body, Present with the Lord, and You Shall Be My Witnesses: Reflections on Sharing the Gospel. Be on the lookout for two additional books that he will soon publish. In addition to his impressive resume, Dr. Gentry proudly served his country as an officer in the United States Army and serves as a martial arts instructor.