A Few Reflections on Schopenhauer

/A Few Reflections on Schopenhauer

David Baggett

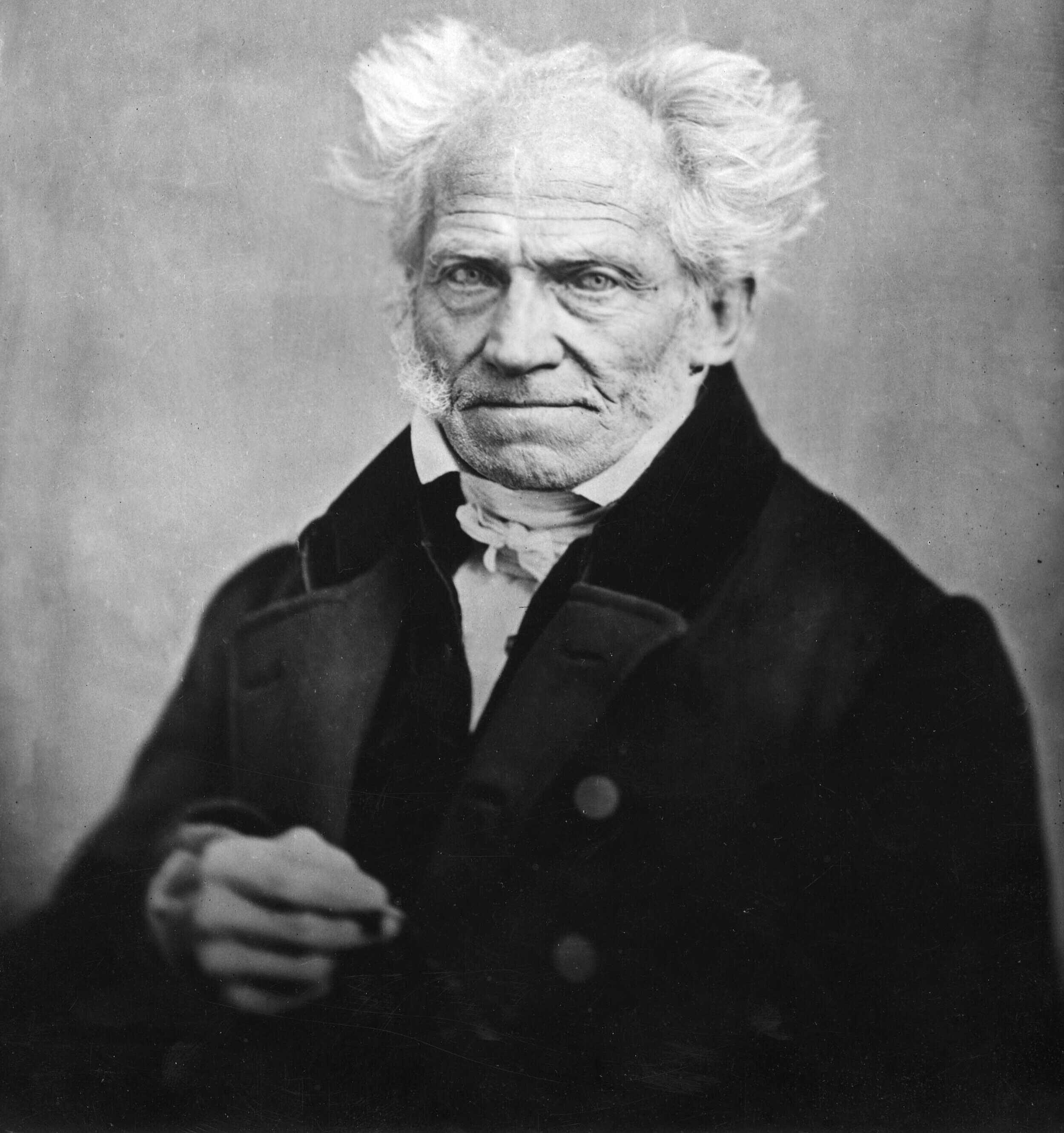

Arthur Schopenhauer’s work had a big influence on Friedrich Nietzsche, especially the latter’s Birth of Tragedy. The similarities between them are numerous, not least the parallel between Schopenhauer’s will and representation, on the one hand, and Nietzsche’s Dionysian and Apollinian, on the other. Both also saw suffering residing at the heart of the human condition, and art as the key to whatever redemption of which we’re capable as human beings. Both came, it would seem, to reject the existence of God; Nietzsche’s bold proclamation of Schopenhauer’s atheism (in The Gay Science) has been critiqued by some for lack of evidence, but it’s generally agreed that many of the implications of Schopenhauer’s depictions of reality are atheistic. At the least God would have been rendered, to paraphrase Laplace, an unnecessary hypothesis.

Much of Schopenhauer’s training in philosophy focused on Plato and Kant in particular, and the latter provided the tools for his metaphysical position, the first of the two big ideas of his magnum opus. Kant’s so-called transcendental idealism wielded a huge influence on Schopenhauer, who was born the same year Kant published his Second Critique. The world and our existence poses a riddle, Schopenhauer thought, in light of the human subjectivity in which we’re trapped. The world as it is in itself is not the world as it appears to us; as a result, everything we experience is mediated by the perceiving subject. We can’t know things as they are in themselves; rather, we can know only our transcendental cognitive framework and the representations it makes possible.

Rather than directing his attention, like Kant did, to what the subject imposes on experience, Schopenhauer instead sought to observe more closely how the subject may be tied intimately with the underlying nature of the world. He looked for an essential homogeneity between the subject and object, and thought the body provided such a link between the inner and outer. The body is not just a spatio-temporal object (something experienced outwardly), but also something we experience inwardly, subjectively, namely, the will. The actions of our bodies are manifestations of our wills.

Schopenhauer even thought that the world as a whole is fundamentally will, offering examples like the following: “The one-year-old bird has no notion of the eggs for which it builds its nest; the young spider has no idea of the prey for which it spins its web; the ant-lion has no notion of the ant for which it digs its cavity for the first time. The larva of the stag-beetle gnaws a hole in the wood, where it will undergo its metamorphosis, twice as large if it is to become a male beetle as if it is to become a female, in order in the former case to have room for the horns, though as yet it has no idea of these. In the actions of such animals the will is obviously at work as in the rest of their activities, but is in blind activity.”

Interestingly, such obviously goal-directed tendencies interwoven throughout nature don’t lead Schopenhauer to affirm teleology in the world, but to deny it. The will in question is characterized as “will without a subject.” Such an interpretation is possible, but it by no means strikes me as obvious or the best explanation. A clear alternative is presupposed in Proverbs 6:6-8: “Go to the ant, you sluggard; consider her ways, and be wise: which having no guide, overseer, or ruler, provides her meat in the summer, and gathers her food in the harvest.” The Bible in fact is replete with lessons about moral or metaphysical truth drawn from garden-variety features and operations of the world. Examples of seemingly teleological instances of the world are an odd choice to drive home a point denying its reality.

Here’s another example Schopenhauer offered: “Let us consider attentively and observe the powerful, irresistible impulse with which masses of water rush downwards, the persistence and determination with which the magnet always turns back to the North Pole, the keen desire with which iron flies to the magnet, the vehemence with which the poles of the electric current strive for reunion, and which, like the vehemence of human desires, is increased by obstacles.” Here he seems to adduce examples of stable natural laws, which, I suppose, can be thought of as evidence of God as a needless hypothesis; but I’m not convinced it’s a good inference. The sort of argument that can be teased out here conspicuously and presciently resembles the suspicion of many today that science and faith are fundamentally at odds, but this seems to be a mistake. Let’s consider just one reason why this is so.

Brian Cutter notes that there are two sides to the human capacity for science: “The first is the fact that the universe is intrinsically intelligible—that nature is structured in a way that admits of rational comprehension…. The second … is that our actual cognitive equipment, such as it is, allows us to discern the broad lineaments of nature, to plumb the deep structure of reality at levels well outside those relevant to life on the savannah. Both of these facts seem much more like what we should expect if Christian theism were true than if naturalism were true. The first fact fits comfortably with the theistic idea that the universe has its source in a Rational Mind, and is really quite surprising on the opposite assumption. And the second fact accords nicely with the Christian doctrine that human beings are made in the image of God, where bearing the image of God has traditionally been supposed to involve, among other things, the possession of an intellectual nature by which we partake in the divine reason.” (See his chapter in Besong and Fuqua’s Faith and Reason.)

On such a view both the existence of stable natural laws and our ability epistemically to access them count evidentially more in favor of theism than atheism, a personal universe rather than an impersonal one. Although an atheist, Schopenhauer may not have altogether been a naturalist, though, because he thought that through art, and music in particular, we can in some sense gain a measure of equanimity in face of the invariable suffering and futility of our lives. Suffering is the norm, he thought, and despite our subjective feelings of willing, we’re not actually free; the sense that we are free is mere appearance.

But rather than leaving us there, Schopenhauer’s second big idea pertained to what we can do in the face of such pessimism. We shouldn’t abandon life itself, but willing in general. Denying the will is the cornerstone of his ethics and aesthetics, and Nietzsche was most struck by Schopenhauer’s aesthetic deliverance from willing. It would seem that Schopenhauer’s notion of will was inextricably tied to notions of futility, of striving, of deficiency, and of suffering. With aesthetic contemplation, he thought, the subject is no longer regarding the object—a beautiful song, for example—in relation to its will. Rather, the object enchants the subject by virtue of its beauty, and as long as it does so the subject’s will is annulled.

In such a situation we find the object beautiful for what it is rather than for its functional capacity, what it does, so willing isn’t needed. The subject thus transcends time and space to realize the eternal realm of a Platonic Idea, and has himself thereby realized his own eternity.

Leaving aside how on earth this shows our “eternity,” two thoughts occur to me here, and with these I’ll end this short analysis. First, his understanding of willing seems flawed, if not idiosyncratic. I don’t feel unfree when I can’t help but recognize objective beauty, or feel the force of a lovely argument whose conclusion is inescapable, or at least eminently reasonable. I rather seem to feel at my most free in such cases. Attentiveness to evidence, apprehension of the lovely, feeling the force of the good—none of these annul my freedom. My freedom most consists in my capacity for just such things!

Just as I don’t see the most salient feature of faith, rightly understood, to be epistemic deficiency, I don’t see the most distinguishing feature of freedom, rightly understood, as existential deficiency. Long before Enlightenment construals of such concepts foisted themselves on us there were traditional understandings of them expressed in quite different terms. The truest freedom, on those more ancient foundations, is to live as we were meant to live; to love the true, the good, and the beautiful because they’re worth loving; freedom from the shackles that would preclude us from becoming fully humanized. So it seems the right goal is not the annulment of our freedom, but its fulfillment, its maximization, which is consistent with constraints to prevent expressions of agency that vitiate rather than conduce to abundant living.

And second, Schopenhauer’s openness to a Platonic paradigm is tantamount to a tacit admission of the inadequacy of naturalism to account for his intuitions here. A personal God strikes me as a better explanation than impersonal Platonic Forms floating in metaphysical limbo; but, while not Christian, Platonism remains eminently congenial to a traditionally theistic understanding of the world. “A Platonic man,” George Mavrodes once wrote, “who sets himself to live in accordance with the Good aligns himself with what is deepest and most basic in existence.”

With his co-author, Jerry Walls, Dr. Baggett authored Good God: The Theistic Foundations of Morality. The book won Christianity Today’s 2012 apologetics book of the year of the award. He developed two subsequent books with Walls. The second book, God and Cosmos: Moral Truth and Human Meaning, critiques naturalistic ethics. The third book, The Moral Argument: A History, chronicles the history of moral arguments for God’s existence. It releases October 1, 2019. Dr. Baggett has also co-edited a collection of essays exploring the philosophy of C.S. Lewis, and edited the third debate between Gary Habermas and Antony Flew on the resurrection of Jesus. Dr. Baggett currently is a professor at the Rawlings School of Divinity in Lynchburg, VA.