My cousin Jay is vacationing on Bald Island. “What’s Bald Island like?’ I wonder. “It’s a tiny island off Carolina Beach, N.C. One takes a ferry to the island; no cars are allowed; one gets around by golf cart. Bald Island is a resort village among forests, sandy beaches with sand dunes and oat grass.”

Jesus broaches with his disciples the subject of the kingdom of God. They’re intrigued. What’s it like? Knowing their interest, Jesus asks, “What is the kingdom of God like?” He reveals to them the Kingdom’s singular code and character. Let me share with you this deep code underneath the Kingdom’s character. Is this code integral to your character?

Jesus reveals to his disciples he’s soon to be rejected, tried, killed, and raised. Physically, he will soon be gone from them. They are to take over His ministry in His absence. The deep code of the Kingdom must undergird their character – and your character.

You are the disciple in His place now. He is speaking to you. You are taking over His ministry in this generation. His ministry must become your ministry. The deep code of the Kingdom underneath Jesus’ character must become yours.

Jesus reveals the Kingdom’s deep, underlying code and illustrates it through parables (stories illustrated with everyday objects and situations). He says, “If any want to come after me, let him deny himself and let him take up his cross daily…Whoever does not carry his own cross and come after Me cannot be My disciple” (Luke 9: 23)

What does Jesus mean “deny himself”? For short, denying oneself literally means, consider “your life as already finished”. Do you reckon yourself already dead? In Charles Dickens’ novel, A Christmas Carol, which we will soon be watching, the hum-bug miser Ebenezer Scrooge has his last Christmas Eve vision. He is taken to the cemetery, and there guided to a particular tombstone. He brushes away the snow where he sees his name inscribed. Aghast, he sees himself already dead. Denying yourself is seeing yourself already dead; your selfish self, the self you privilege, the self you please, the self you put first. Consider yourself now dead…gone…departed. Do you? Will you?

A disciple not only treats him/herself as dead, the disciple also “takes up his cross daily”. Every Jew and Roman of Jesus’ day knew the Roman cross. Julius Caesar lined a two hundred mile stretch of road with crosses bearing enemy soldiers. Criminals were forced to carry their own crosses: they bore the wooden patibulum, the cross piece, over their shoulders to the execution site. If Jesus contemporized it, he might say, “Carry your needle and intravenous line to your lethal injection”. Do you consider yourself dead? Are you carrying your patibulum? Is the code of the Kingdom yours?

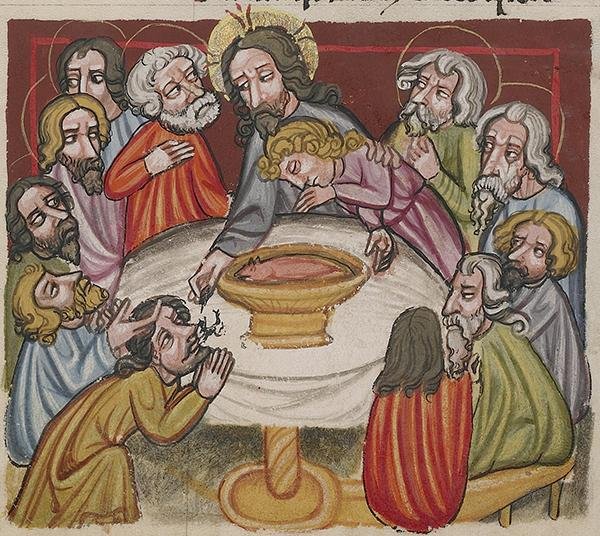

Jesus illustrates the code of Kingdom with the “Parable of the Last Place”. He is in a Pharisee leader’s home for dinner. Jesus notices the invited guests clamor for the seats of honor. Guests semi-recline on couches arranged around the U-shaped tables. At the bottom of the U, is the most honored couch. The middle position of the couch is the most honored place with the person on the left and then the right venerated in descending order. Jesus sees guests scrambling for these choice seats. Have you ever been to a dinner and noticed you are not seated in an honored seat? How did you feel?

In my early ministry, I attended Paul Popenoe’s American Institute of Family Relations conference in Costa Mesa, California. We lunched in a ballroom of round tables. I looked for the table where my favorite speaker was going to sit. I wanted to ‘pick his brain’, so I plopped myself down in an empty seat near his. Very soon, a woman came over to me and said in the earshot of all at the table, “Sir, I’m sorry but this seat is reserved.” Did I feel small. I slinked off to find any seat I could.

Jesus turns to those seeking select seats and says, “When you are invited to a wedding feast, do not take the place of honor. Someone more distinguished than you may have been invited by him, and he who invited you both will come and say to you, ‘Give your place to this man’. In disgrace you will proceed to occupy the last place. But when you are invited, go and recline at the last place. The host may say to you, ‘Friend, move up higher’; then you will have honor in the sight of all…”

Jesus draws this conclusion: “For everyone who exalts himself will be humbled, and he who humbles himself will be exalted.” This is His illustration of the deep code of the Kingdom: deny yourself. Therefore, humble yourself and take “the last place”. Since you consider yourself dead, take the last place! This is the working out of the deep code.

Why does one seek the place of importance anyway? To exalt oneself; to glorify oneself; to try to increase one’s self-importance, honor, fame, position, power or fortune; or to idolize one’s self. This, the Bible calls “pride”. It is grasping glory for oneself and veiled striving to be god. God condemned Lucifer for saying, “I will make myself like the Most High?” (Isaiah 14: 12). C. S. Lewis said, “It was through pride that the devil became the devil.”

Are you tempted to increase yourself? This is contrary to the Kingdom’s code. Jesus’ disciple seeks the last place. Who likes last place? It’s the pokey, cramped, unwanted, and scorned place…the place of self-denial and cross carrying (humility). The early church theologian Augustine said, “The way is first humility, second humility, third humility.” Consider yourself already dead, carry your patibulum, and then take the last place.

In another parable, Jesus further illustrates the Kingdom’s deep code of “denying himself” and taking “up his cross”. Jesus says when you give a great dinner, invite the poor, the crippled, the lame and the blind. They cannot repay you. When we lived in Bristol, England, a couple in our church, the Bucks, gave a Christmas dinner. They had a large, beautiful, eighteenth-century country house. They invited persons without families, persons alone for Christmas, people displaced, or who had sacrificed along the way: a retired missionary; a bachelor, Methodist minister; and American aliens like us.

What do the guests at the parable’s banquet have in common? They are stricken; physically challenged; and radically dependent on others. They are physical allegories, symbols, of disciples who are spiritually destitute and also radically dependent. Disciples recognize their spiritual deficiency in righteousness and absolute dependency for life upon Jesus Christ. These reckon themselves already dead, carry their patibulums to crucifixion, and take the last place.

Tom Thomas

November 2, 2021

All Soul’s Day